A Placemaking Journal

Ready for the Geezer Glut? Then think beyond “aging in place”

Among the Big Issues awaiting communities after we shake off the post-recession blues is what to do about demography. Particularly the part about America’s aging population.

Among the Big Issues awaiting communities after we shake off the post-recession blues is what to do about demography. Particularly the part about America’s aging population.

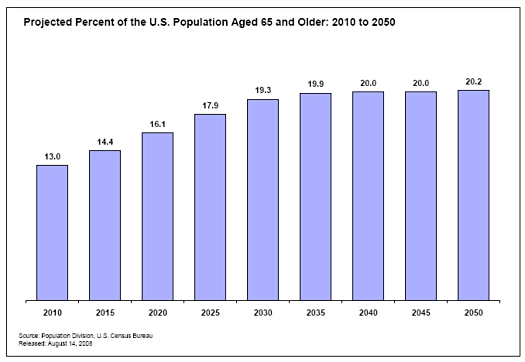

The first-borns among the 76-million-strong Baby Boomer generation reached 65 in 2011. And over the next three decades, the geezer slice of the population pie will swell to 20 percent, compared to a little more than 13 percent in 2010. Take a look at the chart below, compiled from Census projections and pulled from the informative Alliance for Aging site.

That’s more than 88 million folks 65-plus, with the fastest growing cohorts the “oldest-old” segments of 80-plus.

I have a special interest in this topic, given that I’m among those leading-edge Boomers who have reconfigured commerce and culture to suit our tastes over the last half-century. It’s been a great run.

By now, just about everybody not invited to our long-running generational fiesta is tired of indulging Boomer fantasies. Sorry. Since we’re still running lots of stuff and still hoarding most of America’s financial assets, there’s more to come. Currently, we’re in the middle of one of our periodic – and probably our last – reality denial exercises. This is the one where we’re pretending Big Pharma, robots, electric cars and Dr. Oz will extend our playtime into infinity. You know, “60 is the new 40.” Unlike previous Boomer reality ducks, however, this one is going to be tough to buy or lie our way out of.

We’re all gonna die. And before we die, we’re likely to slide into various stages of decrepitude and neediness. We’ve had a glimpse of what that looks like with our own parents. We’re next. So the intricate tapestry of denial we’ve been weaving is already fraying around the edges.

Here’s a taste of how medical professionals are looking at the age wave, courtesy of Ardis Dee Hoven, MD, on an American Medical Association site in 2010:

The statistics are staggering. By age 65, around two-thirds of all seniors have at least one chronic disease and see seven physicians. Twenty percent of those older than 65 have five or more chronic diseases, see 14 physicians — and average 40 doctor visits a year. Situations like these are a nightmare for patients and the physicians who treat them.

Is any community ready for that?

What got me to thinking about this lately were two things. One was a timely diagnosis of the problem, especially as it applies to place, by Linda Selin Davis on The Atlantic Cities October 3 blog. Pointing to “the tainted legacy of age-segregated housing that is a $51 billion industry,” she nailed the unintended consequence of the “retirement community” movement:

We suffer from a severe lack of foresight, a shortage of personal and community planning when it comes to where and how to age. We’ve separated our elders from their extended families without replacing what their relatives might once have provided: a decent quality of life, until the very end.

The other insight feels like a solution, at least in a very targeted way. It comes from organizers of a senior cohousing initiative in Abingdon, VA called ElderSpirit Community. I’ve stayed in touch with them over the last decade because they provide one of my go-to antidotes for cynicism. Starting with few resources and little experience in neighborhood design, finance and development, they’ve assembled and successfully managed the intricate components of intentional community. And they’ve done that while measuring success against wildly idealistic standards. ElderSpirit members committed to a community designed for both physical and financial accessibility, for exploring spiritual purpose in broadly ecumenical ways and for supporting one another’s mental and physical well-being in the final stages of their lives.

While they don’t make a big deal about it, I think one of the advantages ElderSpirit had from the beginning was that key founders were former nuns who had devoted their lives to community development in Appalachian communities. The concept of hopeless causes was beyond their grasp. Plus, it didn’t hurt that they had the organizational skills, discipline and mission focus of Navy Seals.

No wonder then that they learned how to be developers and created an owner/renter neighborhood of similarly inclined folks within a couple years. A half-dozen years after the initial move-in, the ElderSpirit Community now includes 50-plus members, 39 of whom live in units clustered in an infill site within walking distance of Abingdon’s historic downtown and adjacent to the 34-mile-long Virginia Creeper trail for walking and biking.

While a core principle of ElderSpirit was mutual support, what struck me as significant lately is how they’ve evolved a process to take that mission as far as possible without medical intervention. ElderSpirit members are honest with one another about their limits. They are not nurses or doctors and can’t be expected to take on the responsibilities of medical professionals. But as many family caregivers know, the needs of the impaired elderly often have to do with assistance with tasks many of us take for granted – transportation to appointments, meals and light housekeeping, monitoring of medications or just companionship to stave off depression as a result of isolation. Without help, such tasks can overwhelm seniors and turn minor setbacks into complications that threaten their independence and well-being.

Counting on volunteers to respond to those kinds of needs on a random basis doesn’t work. Some folks aren’t inclined to ask for help, so they don’t get it when they need it most. Meanwhile, dedicated volunteers over-commit and burn out quickly. The ElderSpirit answer – and the beginning of a new model for mutual support in community – is a system that matches people, skills and needs.

The community’s Care Committee established sort of a jobs bank of volunteers willing to take responsibility for tasks they felt best equipped to handle – transportation, say, or meals prep. Then they created a sort of buddy system, member-designated care coordinators to tap into the community support network. Each member was asked to pick two care coordinators, people they were comfortable confiding in and trusted to represent them. So when a need arises, the care coordinator activates the network.

That’s exactly what happened when ElderSpirit member Susan Apthorp fell on a patch of black ice and became the system’s initial guinea pig:

(One care coordinator) got people to come to the hospital even before surgery. (Another) put into motion a plan for meals. And pretty much every single person at ElderSpirit got involved in one way or another. I had capes and ponchos loaned to me; large shirts brought to get over my brace; rides to the surgeon’s office; someone helped bath me; someone shampooed my hair. It was amazing. I’d say the system was stellar and something ElderSpirit can be very, very proud of.

Indeed, ElderSpirit is proud enough to be inviting other communities to talk about how such a system might work for them. But for something like this to be replicable, some important foundational components must first be in place.

Remember what Linda Selin Davis wrote in her blog post about “a shortage of personal and community planning.” That’s an understatement. Most Boomers will age in neighborhoods that are unlikely to sustain the kind of care network system ElderSpirit developed. They presume connectivity by car and exile anyone without the ability or desire to drive. The isolation that complicates every challenge in old age is designed into the places most Americans call home.

Arthur C. Nelson, director of the University of Utah’s Metropolitan Research Center, has been hammering away on this point for some time. Between 1950 and 2000, says Nelson, the share of Americans living in suburban areas rose from 27 percent to 52 percent; the suburban population grew by 100 million, from 41 million to 141 million; and suburbia accounted for three quarters of the nation’s population change.

The big push among advocates for seniors has been to build new homes and customize old ones for successful “aging in place.” Almost all of the emphasis has been on universal design, on assuring accessibility in individual homes through design and remodeling choices that make it easier to get around in wheel chairs, reach stuff in cabinets and on countertops and assure safety in bathrooms. But aging in places that isolate seniors in their homes, regardless of how easy it is to climb out of the bath tub, is not going to get at the bigger problem. Especially in an era in which the very demographic forces that have served us Boomers so well turn on us when we need help most. Says Nelson:

The American dream of owning one’s own home may result in millions of senior households living in auto-dependent suburban homes which have lost value compared to smaller homes in more central locations where many of their services will be located.

We all should be for strategies that allow for successful aging in place. But for the strategies to offer meaningful advantages to both seniors and their communities, they have to begin with making the right places.

For more information about the ElderSprirt Community, go here. And for background on cohousing in general, check out the movement’s association site and this previous PlaceShakers post.

Also: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has amassed lots of research about ways neighborhood design and transportation policy affect community health. Go here to plug into those resources. And AARP’s Public Policy Institute provides similar background data and advocacy info. Thanks to the efforts of these and other advocates for more sensible approaches to “aging in place,” we can expect to see these issues rise to the top of communities’ to-do lists over the next decade or so.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.