A Placemaking Journal

Municipal Placemaking Mistakes 03: The importance of a meaningful vision

In our last post in this series, we covered the three steps of placemaking. The first of these steps, crafting a meaningful vision, is the most straightforward, yet it is also the most underleveraged.

In our last post in this series, we covered the three steps of placemaking. The first of these steps, crafting a meaningful vision, is the most straightforward, yet it is also the most underleveraged.

It is underleveraged because communities do not understand its political implications. As a result they do not adequately invest in getting it right.

Mistake #3: Refusing to do the heavy lifting that is required in order to create a meaningful vision.

The political implications of the visioning process matter because real estate development, for better or worse, is a political act in the United States, regulated by the political process.

If you want the politics to work out in your favor, your first step needs to make use of two key techniques:

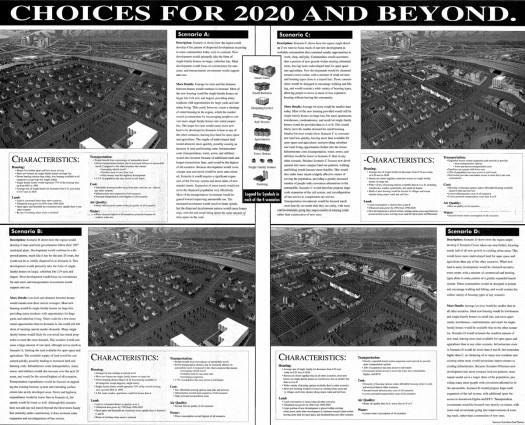

Multiple Scenarios. First, as it relates to the actual physical vision for your community (regardless of the scale — whether it is for the region, neighborhood or block), you need to produce multiple scenarios or options that are different and distinct. At the scale of the neighborhood it is typical for a community to show a scenario that reflects the status quo of a drive-only environment in juxtaposition to a scenario that is walk-able, bike-able, transit-able and drive-able.

Envision Utah provided four distinct visions for how the Wasatch Front could grow over time. They not only described the characteristics, but also illustrated and publicized the differences to the citizens in the region.

Comparative Impact Analysis. Second, you need to provide an analysis of the impact of each scenario through the prism of issues that are important to your community. The five most common types of comparative impact analyses are:

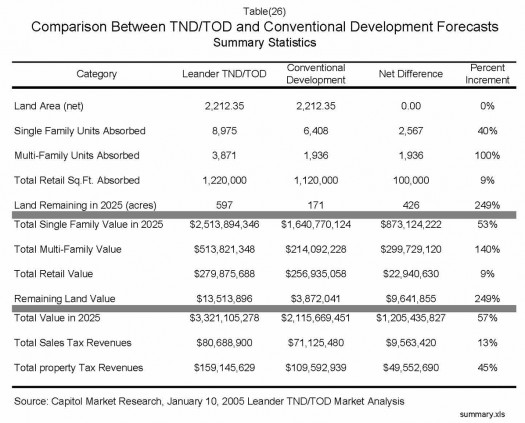

1. Economic. How much will the infrastructure cost to build and maintain under each scenario? What is the expected return on infrastructure investment under each scenario?

This economic impact analysis from Leander, Texas compared the value of development under their existing zoning code versus the proposed form-based code. The difference was 1.2 billion dollars over 20 years so the community moved forward with the update to its laws. Click for larger view.

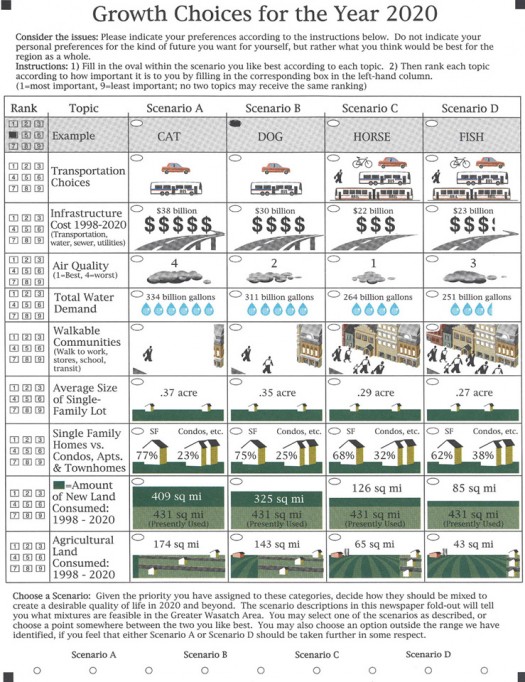

2. Environmental. How does each scenario perform from an environmental perspective? This can include expected impacts on air quality, water quality, resource consumption, agricultural land preservation, etc.

Envision Utah provided multiple scenarios along with the comparative impact analysis in the form of this scantron survey that permitted citizens to select the scenario they preferred. Click for larger view.

3. Health. How does each scenario impact the health of citizens? For example, to what degree will the scenario encourage or permit passive recreation such as walking or biking to your destinations? How will traffic safety be impacted? Consider securing the assistance of your local public health officials who might be familiar with Health Impact Assessment (HIA) techniques that have been created through the leadership of the Centers for Disease Control.

The city of Decatur, Georgia was the first municipality to conduct a Health Impact Assessment

for their Transportation Plan.

4. Visual. Tony Nelessen created the Visual Preference Survey which allows citizens to take a brief survey that rates images of different scenarios on a scale of negative 10 to positive 10. This tool can help quantify the visual impact each scenario will have on the community.

These two images reflect the results of the Visual Preference Survey that Tony Nelessen conducted in Montgomery, Alabama. The results helped build support for Montgomery to

change its laws to make it easier to build the higher rated image.

5. Freedom/Access. How does each scenario impact the freedom of citizens for how they can get around the community? How many transportation options does each scenario produce, and how convenient or efficient are they?

Does it really matter how many meetings you have or how many citizens attend those meetings if you do not provide them the opportunity to make a meaningful choice between different scenarios?

And even if you provide multiple choices, how meaningful can the choice be if it is uninformed due to the lack of comparative impact analysis?

While providing multiple scenarios and comparative impact analysis can improve the quality of your decisions, the overlooked benefit is the political power of those decisions, which manifests in two key ways:

You know you have real political power to fight a bad development proposal when the opposition consists of citizens who are not neighbors to the project.

A meaningful vision that is based upon multiple scenarios and comparative impact analysis protects politicians when they seek to defend the community vision.

It may not be easy producing a meaningful vision, but it will prove the faster way to get you where you want to go, and be more resilient over the long haul, than neglecting this important step.

Series Overview: Through a series of periodic posts, Nathan Norris will explore how cities hinder their own placemaking efforts, wasting time and money by investing in tools, policies and programs that deliver lousy results. In the process, we’ll be looking to you to help flesh out the content through examples, personal experiences and links to additional resources. The goal? A one-stop, crowdsourced primer for cities and towns seeking advantage in an ever-competitive world.

To view the entire series to date, click here.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.