A Placemaking Journal

We’re All Connected: Too bad more is not necessarily the same as better

Roughly two hundred years ago, working in a little Bavarian workshop, Samuel Soemmering created a crude device that, refined by others, would revolutionize communications for the emerging industrial age: the telegraph.

Roughly two hundred years ago, working in a little Bavarian workshop, Samuel Soemmering created a crude device that, refined by others, would revolutionize communications for the emerging industrial age: the telegraph.

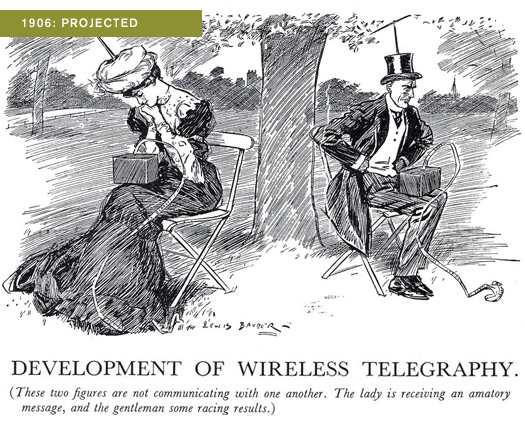

A hundred years thereafter, post-Victorians began to ponder its evolution — wireless telegraphy — in which individuals would receive telegraph messages, printed out on ticker tape, via personal antenna.

And what was their take on such innovation? Did they savor the prospect of a new age of enlightenment, empowered by ever-improving access to information and to each other?

Nope. Instead, they lamented what such a device would do to interpersonal intimacy — with such accuracy that it will boggle your 21st century mind. Consider the two images below: the first from 1906; the second from, oh let’s say, yesterday.

In 1906, “the lady is receiving an amatory message, and the gentleman some racing results” while, in the parlance of our current age, the contemporary image might more likely be described as “this guy’s girlfriend is text-flirting with someone while he’s glued to ESPN.” Either way, it’s an old-timey prophecy come true.

The unsettling way in which we’ve willingly become the punchline in Olde English satire has me thinking again about the nature of connection. As regular Shakers know, connection — and its more intense cousin, interdependence — are, to me, the cornerstone of resilience. In times of challenge or tragedy, all the contingency plans in the world — be they environmental, economic or social — offer little promise without committed, flexible networks of shared interest available to rise up, organize quickly, and implement.

In short, communities with strong social ties fare better in times of adversity.

So today, thanks in large part to the social web, we’re more connected than ever. But has the often superficial nature of those connections made us any stronger?

Social media, for the most part, is characterized by what sociologists call weak ties. You may have 500 Facebook friends, but the number that would actually help you move a couch is considerably smaller. And the number that would help you move a body is considerably smaller than that.

Thus, it’s entirely possible that our hyper-social online world is tricking us into believing we’re connected in more meaningful ways than we actually are. This matters because, for communities to truly thrive over time, two types of connection must also thrive: 1) person-to-person; and 2) people-to-place.

While person-to-person has suffered myriad blows over the past century for a variety of reasons, social media, despite its awkward adolescence, may ultimately prove part of the remedy — a needle towards stitching our social fabric back together. After all, not all online ties remain weak. Some transcend the virtual realm through ever-increasing Meetup type maneuvers that help turn virtual contacts into meaningful, real world friends.

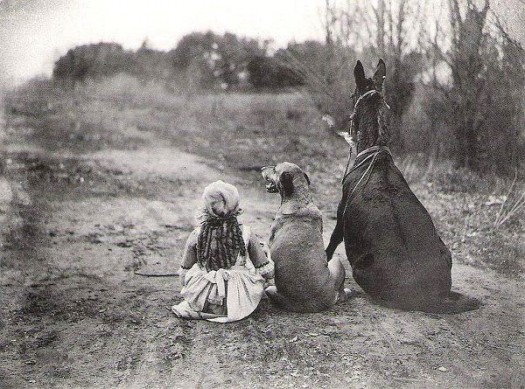

But what about people-to-place? Are our best examples of placemaking, those great everyday places worthy of deep and lasting affection, sufficient to repel the lure of our devices? Can we turn off long enough to fully experience our surroundings? To become vital components rather than mere occupants? To see our built heritage and natural wonders as something more than convenient Instagram opportunities? Consider:

Is the way these people inhabit and reflect their environment…

…comparable to how we do it today?

Does this girl’s connection to the natural world…

…bear any resemblance to this girl’s?

I don’t know. But I do know this: relationships require maintenance. And work. We have remarkable tools at our disposal — light years beyond the magic of wireless telegraphy — but how we choose to wield those tools is a variable. Personally, I believe that if we start with the tool and work outward, our relationships — and with them, our prospects — will whither. Connections for the sake of connecting are worth little more than the effort it takes to click “Friend Request.”

But if we start with our passions and ambitions, our sorrows and joys, our fundamental need for one another, and reach out from there, using whatever tools we find to source and connect with others along the way then, just maybe, all this connecting will actually add up to something meaningful.

The jury’s still out.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.