A Placemaking Journal

Ways to Fail at Form-Based Codes 02: Make it Mandatory Citywide

A while back, we talked about Connections, Community, and the Science of Loneliness, and how our laws have separated not just building uses — residential, commercial, retail, civic — but have also separated people. And that separation has led to a spate of ills — ill health, ill economies, and ill environments. We looked at some of the places that are reversing those use-separated laws of the last 80 years, allowing a mixture of compatible uses where people have a better chance of growing up healthy and aging in place.

A while back, we talked about Connections, Community, and the Science of Loneliness, and how our laws have separated not just building uses — residential, commercial, retail, civic — but have also separated people. And that separation has led to a spate of ills — ill health, ill economies, and ill environments. We looked at some of the places that are reversing those use-separated laws of the last 80 years, allowing a mixture of compatible uses where people have a better chance of growing up healthy and aging in place.

At the end of that piece, I listed ten things that can go wrong with a form-based code. Later we dove into the first of those things: failing to articulate a collective community vision before you can go about the task of changing your out of date laws into a more contemporary form-based code that allows a people to walk to most of their daily needs.

Today I’d like us to talk about point two on the ways-to-fail list: adopt an all-new replacement code without having adequate local support.

Form-based codes (FBCs) can be mandatory citywide, or mandatory just for a certain area where locals want to either encourage something different from what’s happening right now, or preserve and protect existing conditions.

Other places would rather spend less time, money, and political will, and make the FBC optional but incentivized. Incentives may include a shorter approvals process, waived fees, more density, or public-private partnership support structures.

Where the failures come in is when a City tries to make the code mandatory for very large areas, without going through a transparent and inclusive public process that both establishes a collective local vision and agrees on how it will be implemented.

Places that have committed to such a holistic approach are rare, and include Miami, FL; Leander, TX; Pass Christian, MS; Penn, PA; Ridgeland, SC; and a number of new FBCs in Ecuador, including Guayaquil, Puerto Ayora, Puerto Velasco Ibarra, Puerto Villamil, Santa Rosa, and Tomas de Berlanga.

But that’s only 11 out of the 455 form-based codes in process listed on the Codes Study that have undergone mandatory rezoning for the whole jurisdiction. This is a collaborative effort, so please let us know if we’re missing yours.

The reasons most places go with a more incremental approach are myriad, and include time, money and political constraints as well as wanting to encourage growth in areas already served with infrastructure. If you want to really delve into the dynamics, check out this hour and a half discussion led by Jennifer Hurley on implementation strategies.

It’s important to note that optional form-based codes are only optional at the onset. Once a property owner opts in, the FBC is mandatory for them, so it requires some commitment. It also requires some land, usually a minimum acreage of 80 acres, or smaller in an area with generally walkable existing urbanism.

Yet another award last week for Ranson, West Virginia, brings to mind this incremental FBC adoption strategy example. Ranson won multiple grants from HUD, DOT, and EPA to fund a regional form-based code, green streets strategy, and brownfield remediation. Last week Ranson was recognized with the EPA Phoenix Award, for a “fresh take on significant environmental issues, showing innovation and demonstrating masterful community impact.”

Ranson chose to make their SmartCode mandatory in Old Town, where there were many non-conforming lots under the existing Euclidean code, which neither reflected nor supported local character.

This also enabled the redevelopment of six brownfield sites, within frugal adaptive reuse designs using existing buildings and infrastructure when possible.

However, in addition to the Old Town mandatory rezoning, their SmartCode was enabled as an option for the full jurisdiction. Within the G1, G2 and G3 Sectors, developers of 10-50 acres may apply for a Hamlet, or 40-200 acres for a Village. Within the G3 Sector, developers of 80 to 200 acres may apply for a Town Center.

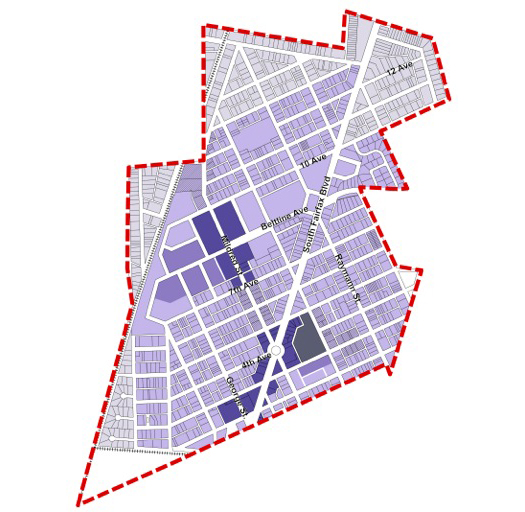

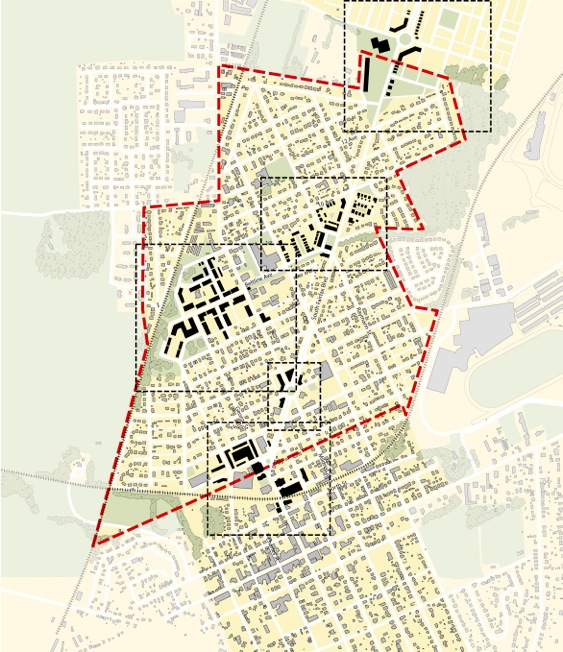

Part of the incentive for developers to use the code was the City being an active planning partner, leading to the rezoning of 1,000 acres of greenfield to the SmartCode. These new walkable neighborhoods respond to the market demand from the DC Metro area, and connect to the passenger rail that serves DC. Below are the Jefferson Orchard zoning map and illustrative master plan, with the gray special district showing some industrial uses around the soon to be relocated Duffields Train Station.

On the far north of the City, Jefferson Orchards has a sector designation of G-3 Intended Growth, allowing for a Village, Town Center or Transit Oriented Development Community Type to optimize the train station relocation, in conformance to the New Community Plan criteria of the SmartCode. This regulating plan demonstrates a Transit Oriented Development in addition to a single use industrial “District.” It should be noted that lot lines and other details are not typically part of a regulating plan, as this plan is demonstrative.

Had the City undergone a mandatory rezoning to a form-based code for the full jurisdiction, they would have also needed to come up with the funds required to retrofit their intended A-Grid into walkable streets in order to make the new buildings’ zero-foot setbacks safe. Choosing instead to concentrate their FBC on the parts of the City with the highest development pressure allows them to bundle their infrastructure investment, create some interesting “seed” neighborhoods, and step into their placemaking role in a way that makes a difference.

And isn’t that what a form-based code’s really all about?

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.