A Placemaking Journal

The Pendulum Shifts: Expertise is now suspect

Slow and steady progress is built on an ongoing series of course corrections. Subtle variations in direction based on new variables, new challenges, and new innovations.

Slow and steady progress is built on an ongoing series of course corrections. Subtle variations in direction based on new variables, new challenges, and new innovations.

As times and circumstances change, some things inevitably become less productive. Or effective. Or conducive to contemporary sensibilities. So, we make changes.

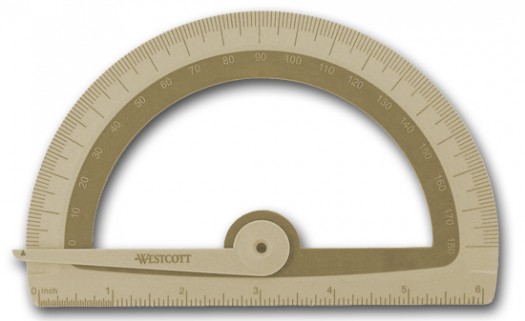

Historically, they’ve been made by a matter of degrees. A minor turn here, a more substantial turn there. But today, in the modern era, we seem overly-fascinated with just one increment in particular. The most extreme increment. 180 degrees.

Out with the old, in with the new.

180 degrees. Can’t get more opposite than that.

Seemingly reasonable

Recently a colleague and friend in the broader placemaking game made a provocative pronouncement via social media:

A community can design their own neighborhood better than outside experts.

Uh-oh.

I get the sentiment. The Modernist revolution, especially as it relates to community planning, ushered in a new era of specialist experts, which was disempowering in two key ways. First, because the entire movement was based on a repudiation of tradition — meaning that things as they’d been done before were now obsolete — the collective wisdom of placemaking, which had been conveniently stored within the common sense of the everyman, became invalid. Which meant that everyday people, who’d somehow managed to build wonderful neighborhoods, towns and cities, were now ill-equipped to do what they had always done.

Then, because there were all new ways of doing things — based in technical, data-driven engineering — the task of community planning became the purview of experts. What people intuitively understood was no longer relevant, and what they tended to know was no longer sufficient.

Perhaps if it had all been a smashing success we’d feel differently but, today, we’re coming up on roughly 75 years worth of built evidence that the Modernist revolution — which, incidentally, was a course correction of 180 degrees — has failed. Our communities have been decimated and we’ve been left with a dysfunctional infrastructure increasingly ill-suited to the challenges that await us in the future.

Hope, however, is not lost. For several decades now, wiser minds have been hard at work unearthing the wisdom of how to build endearing and resilient places and those efforts are now paying off. We’re restoring time-tested models and field-testing new ones, and the practice of placemaking is once again emerging as a people-centric process.

Unfortunately, that’s where things get messy. Because, as we rediscover the value of grass-roots participation, we’re confusing getting back to the base with tossing out the experts. And a whole new, 180-degree course correction is looming.

Not how it worked

Traditionally, everyday placemaking may not have involved experts in planning — as we understand them today — but that wasn’t because experts weren’t necessary. It was because of a key factor that today doesn’t exist: cultural consensus.

That is, we had a general, shared understanding of how to build neighborhoods, towns and cities. We agreed, for the most part, on things like form, architecture, lot placement, street networks, monuments and the prominence of civic institutions. We didn’t need anyone — an expert, for example — to help us understand them. They were a given. But that doesn’t mean that, as a result, we carried on without experts. Not at all. We just engaged different types of experts. Builders, architects, engineers, masons and carpenters. People with the particular skills necessary to, in the context of the times, turn vision into reality.

But today, perhaps because it makes for nice, social-media friendly soundbites, we’re talking about experts as though expertise itself is problematic and that a repudiation of expertise constitutes a return to traditional placemaking. That’s too bad, because it doesn’t. It’s just another out with the old, in with the new overcompensation that will just as painfully fail to address the complexity of our problems.

Magic in the middle

I’ve written before about how planners can better work together with communities towards successful outcomes, as well as the diverse roles — many requiring no expertise whatsoever — to be played in the process. In response to the latter, my fellow PlaceMaker, Ben Brown, did a far better job of articulating my position in a discussion that emerged online:

It’s not a question of bottom-up or top-down. It’s both. It’s always both.

The problem right now is that we have become so annoyed by what we perceive as government corruption and inefficiency at all levels that we’re close to adopting the absurd — and unsustainable — proposition that government is incapable of operating like any other organization. Getting stuff done in every other aspect of our lives, whether it’s entrusting our cars to mechanics or our children to teachers or our bodies to physicians, requires making a deal with others to do work in which we have less expertise. Only when it comes to government functions, like planning, do we deny the possibility that, once we can articulate clear goals, experts can get us where we want to go more efficiently than if we take on the jobs ourselves.

Expertise is just a tool to be leveraged. You want a brick building, you might envision something in particular, or purchase the bricks, or even haul them around the site, but you’d likely still seek out a solid bricklayer to help. You want fine wood detailing, you work with a skilled carpenter. And if your community wants safer streets for walking and cycling, or a new park, or some walkable businesses nearby, or aging-in-place solutions embedded in the neighborhood, it’s equally key to seek out whatever expertise you lack — those skilled in transportation or landscape design, commercial development, neighborhood planning or zoning reform — necessary to empower the effort.

Not at the expense of citizens but in partnership with them. Not exclusively top-down or bottom up, but both.

Such an approach is not disempowering. It’s liberating, because it allows communities to focus on their own expertise — their wants, needs, and concerns — while still leveraging the tools necessary for meaningful implementation.

Those who believed that top-down planning would save us were wrong. But doing an about-face exclusively in favor of bottom-up — in effect, another 180-degree course correction — is no better.

Those who believed that top-down planning would save us were wrong. But doing an about-face exclusively in favor of bottom-up — in effect, another 180-degree course correction — is no better.

It’s just deja vu all over again.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.