A Placemaking Journal

Ways to Fail at Form-Based Codes 04: Don’t Capture the Character

The other day, I was riding my bike from a deeply walkable, bikeable neighbourhood to a more auto-dominated environment, and I was struck again by the tactile response when you’re walking or biking through this change. In the walkable neighbourhood, fellow cyclists were in the streets or in bike lanes, mixing safely with the traffic-calmed cars and frequent pedestrians. But as I moved into the autocentric roads, otherwise law-abiding cyclists take to the sidewalks out of sheer terror at the fast moving cars that often fail to see them.

The other day, I was riding my bike from a deeply walkable, bikeable neighbourhood to a more auto-dominated environment, and I was struck again by the tactile response when you’re walking or biking through this change. In the walkable neighbourhood, fellow cyclists were in the streets or in bike lanes, mixing safely with the traffic-calmed cars and frequent pedestrians. But as I moved into the autocentric roads, otherwise law-abiding cyclists take to the sidewalks out of sheer terror at the fast moving cars that often fail to see them.

And pedestrians? They become scarce to nonexistent.

At this juncture, it’s easy to see the character shift. Walkable places have quiet streets where cafés and stores pull right up to the sidewalk, with offices and homes conveniently above. Schools, parks, and places of worship are nearby.

Driveable places have busy arterial roads where large buffers are needed between the fast-moving cars and nearby buildings. Signage gets bigger and brighter because people pass by faster and with more distractions. Buildings get further apart, surrounded by seas of parking. You move from slow urbanism to fast suburbanism.

You can see why getting out of character in this environment might prove fatal.

Continuing our series on ways to fail at form-based codes, today we examine failure to capture local character within the code’s basic metrics, or other number errors like wide fast streets near small setbacks.

One of the sneakiest problems with a form-based code is getting the metrics wrong. While everything else about the code may look right, and even pass the test for FBCI Criteria, a hybrid-gone-wrong can originate with something as simple as street widths.

It’s important to understand that 99% of the 480 form-based codes on the Codes Study are hybrids in the sense that the FBC covers a limited portion of the city, while the older Euclidean use-based code covers the remainder. This hybridization works just fine as long as those borders are clearly defined. However, when the typical use-based streets get mixed with form-based sidewalks and setbacks, accidents happen.

A FBC with a conventional thoroughfare configuration is a recipe for disaster, literally, as an otherwise walkable environment is threatened with fast cars. A 36’ wide road will have 487% more accidents than a 24’ wide road, according to Peter Swift.

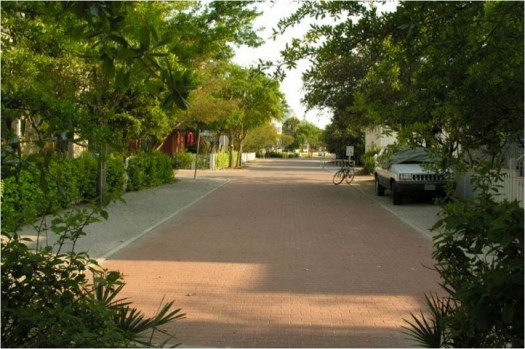

Just a 1’ difference in lane width can often make all the difference in the feel of a place. Like where Odessa Street goes from Seaside, Florida, with 9′ travel lanes, to WaterColor, Florida, with 10.5′ travel lanes. Photos below courtesy of Rick Hall.

However, in most cities on this continent, you can look at the difference between the walkable places with 9′ travel lanes, and the suburban places with 11′ or 12′ travel lanes, and it’s a drastic comparison. For a nuanced Western Canadian metric perspective, see Geoff Dyer’s Walkable Streets: Considering common issues.

I’m not saying that all travel lanes should be 9’. I am saying that streets need to change their character while moving through the rural-to-urban Transect. Within this Transect, there should also be a more walkable A-Grid, and a more service oriented drivable B-Grid. More on that from Geoff Dyer’s B-Grid Be Good.

Another key technical factor to get clear on in your FBC is the front and the back of the building. Conventional development has been confusing the two for the last 80 years, so it’s an easy trend to creep into your code. FBCs must be clear about private frontages, parking location standards, and frontage buildout minimums.

Using conventional tools for density control, such as Floor Area Ratio (FAR), are not necessary or appropriate in a FBC. FAR is the most unpredictable planning tool available, and problematic when embedded in a FBC. Instead, building envelope is managed through height, setbacks, lot width, and block perimeter. Parking requirements further limit density.

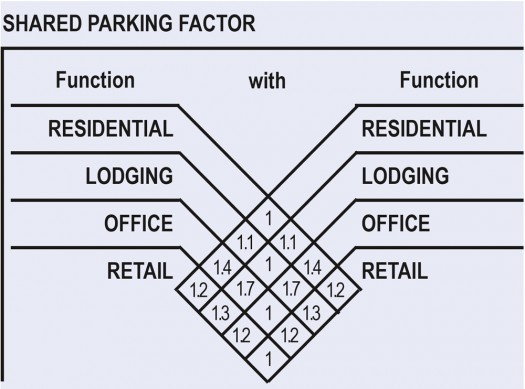

Over parking is one of the critical legacies of sprawl and should not insinuate itself into a FBC. Parking standards must be appropriate to the level of urbanity. While providing adequate parking is necessary in low-density, auto dependent areas, in walkable, mixed use areas, shared parking factors lessen parking requirements. Homes or lodging near offices get the biggest shared parking benefits.

Of course, getting all these numbers right in your form-based code also means getting the sequencing and ownership right. Scott Doyon and Nathan Norris wrote about this last October, in their Chicken or the Egg: Who takes the lead on incremental suburban retrofitting? In auto-centric places where streets and infrastructure lack any sense of meaningful pedestrian amenity, who should take the lead on turning things around?

Increasingly, form-based codes are focused on infill and redevelopment. To make the sequencing work within this more challenging development environment, FBCs often carry with them resilient implementation strategies that include financing plans and public-private partnerships (PPPs).

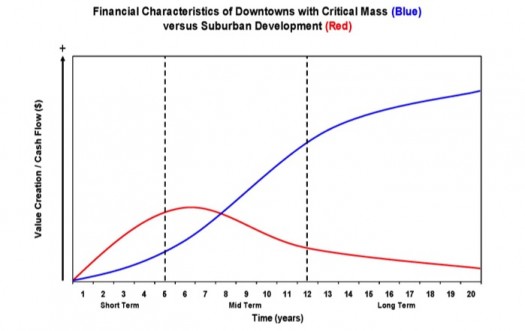

The following chart looks at value creation divided by cash flow, showing the sorts of places that form-based codes build in blue, and suburban development in red. These PPP structures put in supports for the first seven years to allow the form-based development a chance to grow up.

Welcome to the Future: The New Standard Product Types, 2012 by Chris Leinberger, Brookings Institute, and LOCUS: Responsible Real Estate Developers and Investors.

So back to the original question of getting the numbers right on a form-based code. The first step is to measure the local Transect Zones that are delivering the most to the economy, society and environment. We use a tool called the synoptic survey to measure every little detail of these places, from street widths to sidewalks to densities. Read all about how to do that with Susan Henderson’s iPad app here. Then we enable a mixture of compatible uses in keeping with this highest-performing local character.

And if you want more help getting your numbers right, join Susan Henderson, Andrés Duany, Stefanos Polizoides, Matt Lambert, and me in two weeks at CNU’s 202E for a SmartCode Calibration Workshop. Do your homework by listening to this video with Susan Henderson walking you through a Salt Lake City Synoptic Survey.

While you’re there, check out the full CNU 21 Living Community with plenty of form-based coding ideas. And you may as well stay for the free SmartCode Live evening lecture series.

I’m interested to hear your most – or least! – favourite FBC numbers in the comments below!

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.