A Placemaking Journal

Are We There Yet? Affordability in the ‘New Normal’

Pretty soon we’ll have something like a decade of experience in losing our innocence about housing affordability. Isn’t it about time we got over it?

Pretty soon we’ll have something like a decade of experience in losing our innocence about housing affordability. Isn’t it about time we got over it?

For a good part of the last century, we trained generations of housing consumers and housing enablers to buy and sell into what Chuck Marohn calls a “growth Ponzi scheme.” It was fun while it lasted, allowing a lot of us to postpone paying the tab for our delusions to some unspecified date in an imaginary future. Then we got to the real future.

Only now, some five years after the Great Recession was supposed to have ended, are we beginning to sort out its longer term impacts. Here’s what seems already obvious:

The ways in which we’ve designed, financed, constructed and regulated land use development need some serious tweaking if we’re to align the ambitions of families and businesses in the new era with the infrastructure of community essential to their success.

The trouble is, investing so much of our energy and so many of our resources in fine-tuning the Ponzi scheme has left us bummed and broke. If only there were some quick and easy way to reverse the trend and put us all back on track to enjoying the happiness and prosperity we were deprived of during the recent unpleasantness.

Well, good luck with that.

The unfortunate convergence of a slow economic recovery and even slower-witted politics inhibits the Big Fix. Better to get busy on right-sizing our ambitions, particularly if we can model solutions on a smaller scale likely to inspire replication on grander scales. Because so many see it as crucial to a turnaround, affordable housing is a great place to start.

Let’s begin with correcting the Ponzi-era thinking that affordable housing is all about slashing housing costs. Raising affordability by lowering the quality of design, construction, materials and location is a race to the bottom.

And while we’re at it, let’s don’t limit the goal to making only home ownership affordable. Subprime lending practices, the global securitization of bad paper and all the other strategies to put everyone with a pulse into a home they might not be able to afford worked those angles to the max. Which turned out to be not such a great idea.

A goal worthy enough to inspire the effort to achieve it should be something like this: To make living and working in a highly desirable community within reach of the broadest possible range of incomes.

That means addressing affordability with comprehensive strategies, including those related to neighborhood location, transportation/transit choice, energy costs, zoning and building codes, financing and everything else likely to affect household budgets. A dollar saved in any of these categories is exactly equal to a dollar saved on mortgage or rent payments. So why calibrate community affordability exclusively on the basis of price per square foot?

If a sense of urgency is required to get us moving, we’ve got it. The data is long since in. We pointed to the work of others here, here and here, for instance. And just last week, “creative class” cheerleader Richard Florida reemphasized the gap between demand and supply of housing at the right price points and in the right places. Here’s Florida:

Indeed, what we’re currently going through is not a typical housing cycle, but what I have termed a “great reset.” The reset includes increased demand for housing in large, dynamic metros—especially knowledge-based ones—slack demand in older metros and exurban locations, and increased demand for locations at or near the urban core and walkable suburbs serviced by transit.

The “reset,” says Florida, includes “a shift from homeownership to renting, especially in highly priced, dynamic markets on the East and West coasts. The rate of homeownership has been falling since the crisis, and in some of the densest and pricier metros, it’s already below 60 percent.”

And instead of bemoaning the undermining of the American Dream of home ownership for all, we should maybe think of this trend as hopeful, Florida says:

This shift from homeownership to rentals can be a good thing. My own research indicates that metros with the highest rates of homeownership (say, in excess of 60 to 80 percent) also have the most sluggish rates of innovation, productivity and economic growth, while metros in the range of 55 to 60 percent homeownership have faster rates of innovation and growth. A balance between renters and homeowners, then, seems to provide the flexibility of housing types needed to support more dynamic economies.

Viewed in this more comprehensive way, affordability is an issue for not only those whom we tend to see as customers for affordability programs and projects — the poorest among us. It’s about expanding choice for the majority, including those with middle class status and membership in the two largest generations in history, Boomers and Millennials.

We’ve heard plenty about the game-changing impacts of Boomers’ decisions to downsize into city condos and apartments or to age in place — even in ‘burbs where aging comfortably will be tough. For a take on the potential impacts of the younger generation on housing supply and demand, check out last week’s posts here and here from The Washington Post’s Emily Badger and Dina ElBoghdady.

So we have a glimpse of what’s coming. Demographic change, combined with economic pressures left over from the recession, will challenge communities to accommodate the reset Florida predicts. And we know it’s unlikely, given what’s going on in Washington and state capitals, that we’ll get sweeping, top-down policy innovations, accompanied by hundreds of billions of dollars in planning and infrastructure funding, to ease the transition. No Big Fix.

Which means local governments, businesses and citizens are stuck with developing and implementing low-budget coping strategies that are, at the same time, responsive, comprehensive, and replicable. Where to start?

Maybe by picking the right places to do small-scale good work that can leverage big change in the right direction.

In a popular “Better Cities & Towns” post last week, Rob Steuteville called attention to a multifamily project in Chico, CA designed by Anderson|Kim Architecture + Urban Design and developed by Tovey Geizentanner of Chico Green line Partners. It’s a four-building, 22-unit project that completes a TND called Doe Mill that’s been in the works for a decade and a half.

The designers are well-known and admired New Urbanists who brought to the project the attention to site planning and architectural detail their colleagues admire. Yet what drew Steuteville to the project was its context — classic suburban sprawl miles from Chico’s walkable downtown.

What makes the example a worthy one, Steuteville argues, is its strategic opportunity. Demand will drive development in Doe Mill’s direction. By getting a lot of other stuff right — including aligning affordable scale with design worthy of high-end, mixed-use infill in town — the designers and developers established a standard for future growth along the same corridor:

Rather than contributing to the sprawling character of this area, these buildings help to set a new pattern. The retrofit of our suburbs will be an important land use and planning task in the coming years, and the completion of Doe Mill gives Chico an example of how to do better.

The project is also an example of what it takes, in the new era, to achieve what firm partner John Anderson defines as “ROBD,” Return on Brain Damage. For the local or regional developer, Anderson says, there are already enough regulatory, financial and project management obstacles to threaten solvency. Best to pick places and projects that match developers’ capacities and leave the complex, resource-draining projects to big firms with the staffs and overhead margins to compensate for the headaches.

Here’s another reason for cherry picking neighborhood-seeding opportunities outside the most intensely developed urban cores: These opportunities most often present themselves in places that make up the majority of America’s landscape, from historic streetcar suburbs all the way to the totally sprawled-out, totally car-dependent developments that still count as urbanized areas in the U.S. Census.

Expanding walkable mixed use and transit to the residential monocultures of the ‘burbs, similar to the Doe Mill strategy, is one way to get a little closer to the goals of community affordability. Another is to add to residential affordability, including rental affordability, in close-in neighborhoods where the appeal of amenities like transit and walkable access to daily needs have driven housing costs beyond the reach of lower and middle-income families.

In the desirable in-town neighborhoods, the affordability challenge has a lot to do with managing the costs — and what Anderson would characterize as the brain damage — of politics and permitting. The more appealing the infill site, the higher the likelihood of push-back from well-organized, politically influential groups who prefer the property remain undeveloped or be developed in ways that so limit the ROBD for property owners and developers that it becomes impractical.

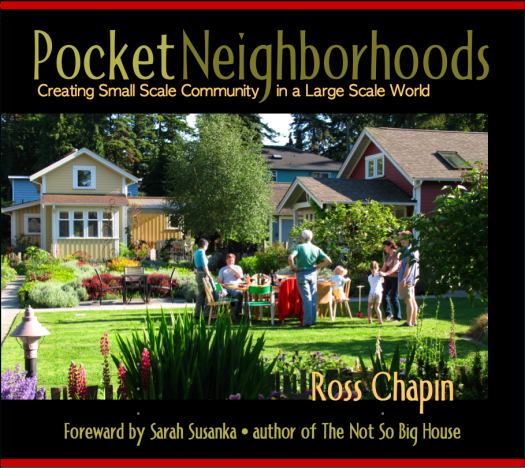

Superior design can help. Ross Chapin, who pioneered “pocket neighborhood” development in the Pacific Northwest, is the ace at demonstrating that well-planned and executed clusters of small-scale housing can not only overcome resistance to density and predispositions about the inherent value of bigness, they can command a premium in a local real estate market.

Often, however, while quality design is a necessary condition, it’s not sufficient for achieving success at infill affordability. It helps to have a hurricane.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina provided the sense of urgency necessary for a temporary suspension of business as usual in the hardest hit areas of Mississippi and Louisiana. You can read about Katrina Cottages and their influence on FEMA’s one-time-only experiment with alternatives to FEMA trailers here.

Out of that came architect Bruce Tolar’s Cottage Square in Ocean Springs, MS, then an adjacent neighborhood of rental cottages, then one of single-family units raised above the flood zone in Pass Christian, MS. Some 70 units altogether, all in close-in locations where residents can get along without cars should they wish and all representing neighborhoods and individual homes so appealing that their communities are proud to have them.

Tolar is a design consultant in the post-Sandy neighborhoods of New Jersey, expanding a network of support that has already enabled models for desirable, affordable infill and that likely represents the way to refine and expand the strategies in the near future. To grow the model beyond Cottage Square, Tolar partnered with a regional non-profit, Mercy Housing and Human Development, and a local developer. Between them, they had the skill sets and connections to maneuver through the financial, regulatory, design and construction challenges that might have overwhelmed any one of the partners acting alone. Now, Tolar’s working with a national non-profit, Next Step, to apply the public-private partnership lessons on the New Jersey Shore and beyond.

This is the way a lot of good work is going to get done in the interim between unsticking real estate development from outmoded ways of doing business and whatever comes next. The transition is slow and painful, especially for those in most need of affordable access to opportunity in the new era. But there’s no ignoring the affordability problem, now that its implications are apparent in every measure of recalcitrance in the economic recovery.

If you want to join in a discussion about these topics, I’ll be with Ross Chapin and San Francisco planner Maia Small in a NOVEDGE Google+ Hangout on Tuesday, July 29, from 2 to 3 p.m. ET. Register here.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.