A Placemaking Journal

Disappointment, Pessimism, Rage: Is this America at middle age?

Still wondering about why it’s so hard to have a civil conversation about planning for the future in so many places? Or why everyone seems so pissed about everything all the time?

Still wondering about why it’s so hard to have a civil conversation about planning for the future in so many places? Or why everyone seems so pissed about everything all the time?

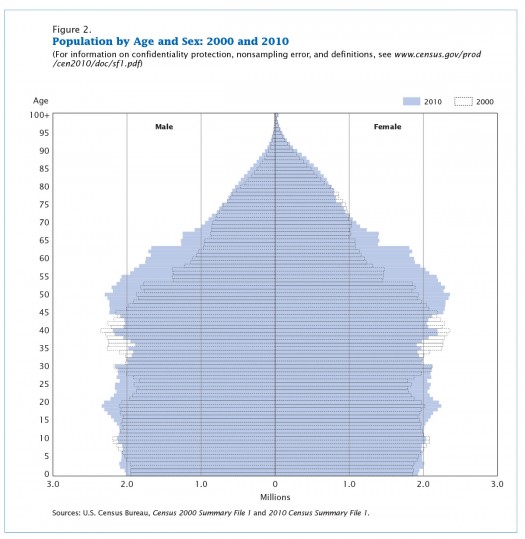

Could it have something to do with the telltale bulge in the waistline of American demography?

Currently, the most populated age ranges in America are those that represent folks in their 40s and 50s. Which, coincidently, are the ages at which mid-life crises typically undercut hope and optimism. Is the Age of the Bummed Out all about the ages of the bummed?

I like the sound of this argument for a couple reasons. First off, it doesn’t make my head hurt trying to understand all the complicated forces at work. It’s simple: It’s a phase. And there are charts.

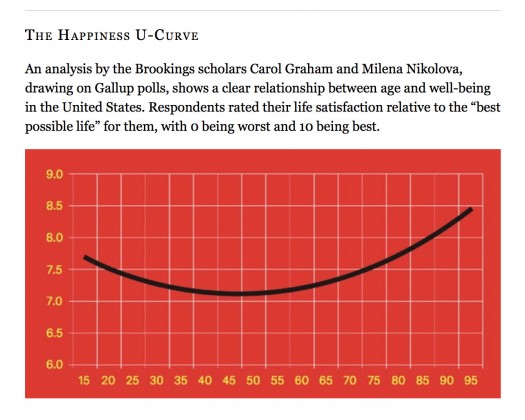

If we need some social science to prop up the speculation, Jonathan Rauch obliges in his November 17 piece in the Atlantic. In one bit of evidence, Rauch references an international survey that “asked people in 149 countries to rate their lives on a zero-to-10 scale where 10 ‘represents the best possible life for you’ and zero the worst. They found a relationship between age and happiness in 80 countries, and in all but nine of those, satisfaction bottomed out between the ages of 39 and 57 (the average nadir was at about age 50).’

“In other words, if all else is equal, it may be more difficult to feel satisfied with your life in middle age than at other times.”

What Rauch and the researchers suggest is something like this: When we’re in our 20s and early 30s, we’re busy building careers and families. We have aspirations, some of them connecting to materialistic and egoistic benchmarks — money, stuff, professional recognition. Then, as we approach middle age, we either hit the benchmarks, only to discover we’re not experiencing the happiness we expected, or we don’t, and we can’t fight off feelings of disappointment in ourselves. “In other words,” says Rauch, “middle-aged people tend to feel both disappointed and pessimistic, a recipe for misery.”

So now back to the charts:

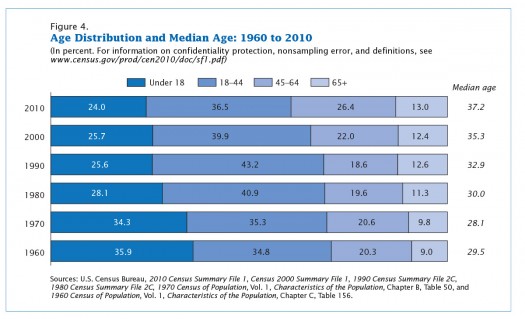

Thanks to the aging of the Baby Boomers, America’s median age has climbed from just under 30 a half-century ago to just over 37 in 2010. The 45-plus population is the only age group to grow its percentage of the population since 1960. And within that 45-plus age group, it’s the 45-64-year-olds that represent the biggest population segment.

As a nation, we’re at peak mid-life crisis.

Now, I don’t want to implicate Jonathan Rauch in my argument for linking a grumpy life stage in individuals with a grumpy stage in American politics and culture. He sticks to the research-driven, life stage discussion. But here we are with all these middle-aged people at a time in their lives where they’re statistically vulnerable to the existential blahs. And here we are as a nation, stuck in the existential blahs.

Just sayin’.

There’s another good reason for my attraction to this framing of the issue. And there’s another chart, thanks to Rauch and the researchers he quotes:

Click for larger view. Credit here.

They call it a “U curve.” I think of it as a smile curve. Kind of a Cheshire Cat smile. It suggests life dissatisfaction bottoms out and starts heading in the other direction when folks get a few more years on them.

It’s not that the after-50 crowd suddenly reclaims the optimism of their 20s. Rather, says Rauch, “midlife is, for many people, a time of recalibration, when they begin to evaluate their lives less in terms of social competition and more in terms of social connectedness.”

You know, like social connectedness in community. Less “me,” more “we” — as I tried to suggest here. And that’s got to be good news for those of us in the business of addressing the desire for connectedness in the design of the built environment.

It would be swell to imagine that all we have to do is wait out the smile curve.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.