A Placemaking Journal

Urbanism: Nothing to Fear

When the 9/11 attacks happened, all sorts of pundits started re-questioning whether cities should be decentralized, notably including Ed Glaeser. That questioning happened again after Hurricane Katrina and the continuing hurricanes along the Gulf Coast.

When the 9/11 attacks happened, all sorts of pundits started re-questioning whether cities should be decentralized, notably including Ed Glaeser. That questioning happened again after Hurricane Katrina and the continuing hurricanes along the Gulf Coast.

Keep in mind that in prior centuries recessions, depressions, and crashes were known as “Panics.” In Franklin Roosevelt’s first inaugural speech the memorable line is, “Nothing to fear but fear itself.” Roosevelt himself did not have strong opinions regarding urbanism, and in fact was suckered into “authoring” the Bureau of Public Roads’ (now the USDOT’s Federal Highway Administration, back then it was in the Dept. of Agriculture with a mission of expanding farm-to-market access) Free Roads and Toll Roads white paper, which made the case for accelerating limited access freeway construction as a means of helping cities remove “decrepit” (they meant dilapidated) parts of their economies — the chapter on cities is notable for warning Congress that some local officials had redevelopment ideas of their own!.

The forces for dispersal were many, but at their root was the failure to recognize the existing and potential assets of urban places. The conversations at the time — whether about public health, design, or economy — stressed the assumed benefits of dispersion.

All of this, I think, presents a different narrative than the one around how highway development increases future value of low density land for residential and commercial developers. That’s true but the precipitating events may have had more to do with a deliberate strategy of redefining the military defense-ability of the economy.

With a massive conversation starting about the 21st century economy, we have a great opportunity to revisit all this.

This piece by Peter Galison comes closest to putting this in a new urbanist context, although a Grist piece last week by Heather Smith brings it up to date. Notably part of the Cold War logic was to see U.S. cities as vulnerable due to their economic diversity and centralization, and from the late 40s through the 1950s cities and regions received “how-to” technical assistance on industrial decentralization along with a low-profile set of tax benefits for manufacturers to accompany the better known carrots of highways and infrastructure.

Advanced manufacturing and the tech sector, left to their own devices, won’t necessarily rediscover cities. Google is sort of there, Apple is not. Millennials are, but most cities are making it hard to provide housing they can afford. Detroit ends up being a great place to visit but hard to find a place to live. Even in Baton Rouge, city development policy is WAY behind market preference, making it hard to see that the tech sector is starting to express preference for central locations.

Developments along the US borders of Mexico and Canada are designed with imports in mind, a kind of one-way economy. In the real estate industry, mega-brokers have pushed the idea of “inland ports” as one-way distribution centers covering thousands of acres to facilitate quick, even same-day delivery of both consumer and business-to-business demand; in the other direction railroads are shipping out what we’re exporting, mostly commodities (oil, chemicals, fracking sand, food, vehicles and scrap materials—the latter of which is fueling Asian production for which US industries are paid $50/ton and we ship back I-phones and equipment at $2000-$10,000 per ton, and call it “economic development.”) But the conversation is switching back to a “Made in America” ethic, looking for opportunities to nurture local markets. How do we re-target the capacity of inland ports, transportation hubs, and industrial parks to connect to and contribute to the larger economy in both directions?

Across this continent, we are starting to figure out how I-Zones are a gateway to reintegration of a complete and more urban economy, with the help of zoning reform. I-Zones are keyed to industry and employment intensity, to establish a light-to-heavy industrial spectrum, connected with nodes of walkable worker villages. They work in a similar way to how T-Zones, or Transect Zones, are keyed to residential density to establish a rural-to-urban spectrum.

Worker village provides services to surrounding heavy industrial in a walkable Main Street format. Image credit: Rural Municipality of Rosser, Manitoba, via PlaceMakers Canada Inc. and MMM Group.

Key to I-Zones is a street overlay of 1. Walkable Streets, 2. Active Transportation Corridors, and 3. Industrial Corridors. Image credit: Rural Municipality of Rosser, Manitoba, via PlaceMakers Canada Inc. and MMM Group.

Keep in mind that Centreport is in a “rural municipality” less than 10 km from downtown Winnipeg, adjacent to the regional airport; yet the optimal solution to workforce access and traffic management is urban form along the edge, and the optimal solution to manufacturing supply and shipping is intermodal (truck and rail) with distribution and heavier uses further back around a common-use (providing access to Canadian National + Canadian Pacific Railway + Burlington Northern Santa Fe) rail terminal.

T-Zones work quite well in industrial neighborhoods where the industry is light and green enough to allow residences to be fully integrated, like in parts of Berlin or where industrial complexes are not part of extensive inland ports where rail and truck transport dominates, like in parts of El Paso.

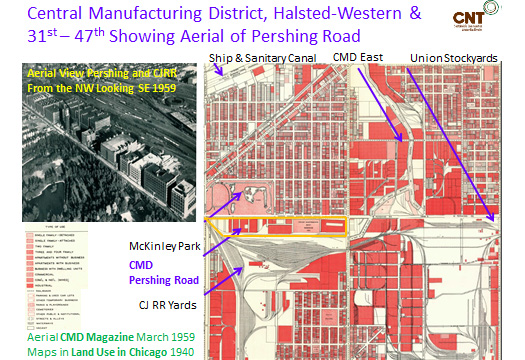

Perhaps we can still learn something from America’s first planned industrial district, the Central Manufacturing District or CMD. Built by the owners of the Chicago Stockyards when that ran out of room in 1905, it accommodated hundreds of premier manufacturers through integration with adjacent neighborhoods and their grids along the frontage; using buildings that could be individually entered instead of centrally gated; with offices and reception in the front, light manufacturing within; rail-linked loading docks in the rear, all sharing a joint-use rail facility connected to all 32 “trunk” railroads, followed by heavy manufacturing behind the rail junction. One thing you won’t see in this 1959 aerial is parking—commuting was by walking and mass transit; and another is the underground network of the facility’s own power plant and distribution system, and underground service tunnels. The Stockyards + CMD employed 40,000 workers in less than a square mile and did so without avoiding urban form. Modern inland shipping technology already allows 40-185 acre freight terminals to deliver capacities that typical “inland ports” can only meet on thousands of acres—one of these is urban, and one is not.

Your grandfather’s industrial park: Birds-eye View of the Central Manufacturing District from CMD Magazine 1959.

In areas where residential is discouraged because of heavy industrial or flight patterns, I-Zones work to cluster development and still offer up a modicum of placemaking in an environment dominated by trucks, trains and airplanes. While the dispersed city was driven in part by the desire to make cities into less of a bomb target that would disable the military machine, issues of wellbeing and resilience are making the case for reintegrating manufacturing and its workforce and supply chains into complete, compact, connected urban patterns.

As the saying goes, we live in interesting (and challenging) times. Whether the next threat is military, economic or ecological in nature, the ability to adapt quickly and efficiently is nowhere more important and achievable than in our place-based designs.

We’ll keep talking about this in an upcoming Placemaking@Work webinar and at CNU 23.

–Scott Bernstein

Scott is President and CEO of The Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT). The CNT is the national non-profit that has pioneered ways to quantify the advantages of linking transportation, land use and housing strategies with economic development and community affordability. It is the leading national provider of web-based analytic and data access tools for local area planning intended to meet the triple bottom line of improved quality of life, improved economic quality of place, and environmental resilience. CNT is a winner of the 2009 MacArthur Foundation Award for Creative and Effective Institutions, and Planetizen lists Scott Bernstein as number 27 in its poll identifying the Top 100 Urban Thinkers of the past century.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.