A Placemaking Journal

Stay Hungry. Stay Foolish. The DNA of urban succession

Steve Jobs ended one of his most memorable speeches with the encouragement, “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.” He was quoting the message on the final page of the final publication of The Whole Earth Catalog, Stewart Brand’s version of pre-Google, assembled with typewriters, polaroid’s and scissors. Jobs’ point for me was to realize that the hunger for knowledge is not neediness, powerlessness, or weakness, but rather is a transformational driver of change and growth. An essential part of wellbeing.

Steve Jobs ended one of his most memorable speeches with the encouragement, “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.” He was quoting the message on the final page of the final publication of The Whole Earth Catalog, Stewart Brand’s version of pre-Google, assembled with typewriters, polaroid’s and scissors. Jobs’ point for me was to realize that the hunger for knowledge is not neediness, powerlessness, or weakness, but rather is a transformational driver of change and growth. An essential part of wellbeing.

With the beginning of springtime, I’ve felt the need to return to the yoga mat to offset the effects of running again – and aging! Although I used to teach yoga long ago, after not practicing regularly for 8 years, I feel like I know nothing. That experience of “the beginners mind” of hungering for knowledge is delightfully poignant and pertinent to many of the community conversations we have here. While the Hindu and Buddhist teachings that guide yoga may encourage us to let go of need and desire, the “Stay hungry, stay foolish” message is a different sort of force that keeps us returning to the mat with a beginners mind.

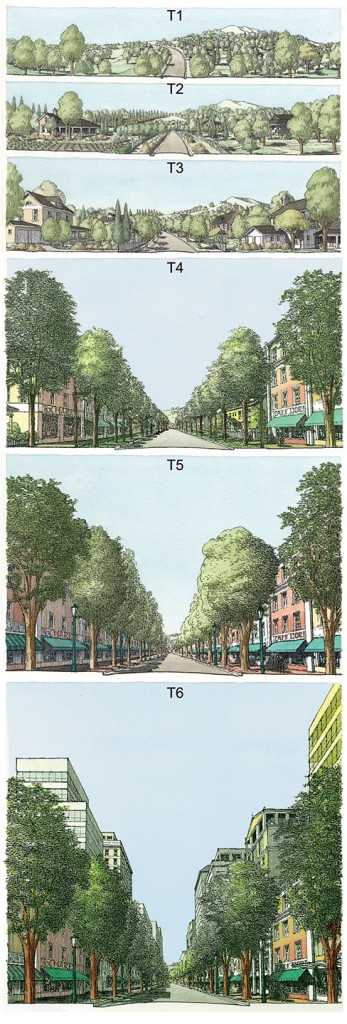

What brought this all up was having the privilege of working with Andrés Duany again last month. As he talked about the successional Transect, he pointed out how important it is to not design for the climax condition if today’s marketplace supports something less. “Even New York City was once a shantytown.” Not that every rural hamlet aspires to grow into a city, or even a town, T-zones are meant to allow character-appropriate evolution over time. The Center for Applied Transect Studies (CATS) puts it this way:

“The Transect is a progression from rural to urban, but it also has a temporal manifestation. This series can be understood as a city maturing as certain zones become more urban over time. This is analogous to the ‘successional’ concept in nature in where grassland prairie gradually evolves to woodland, and then to a climax forest. In urbanism, the climax would be the equivalent of an area designated for historic preservation.”

“The Transect is a progression from rural to urban, but it also has a temporal manifestation. This series can be understood as a city maturing as certain zones become more urban over time. This is analogous to the ‘successional’ concept in nature in where grassland prairie gradually evolves to woodland, and then to a climax forest. In urbanism, the climax would be the equivalent of an area designated for historic preservation.”

However, most of the zoning and subdivision laws governing North America do not enable the Transect, but instead they promote auto-centric development patterns. Andrés points out, “Auto-centric development destroys human habitat, society, trust, flexibility, and resilience. Plus, instead of becoming successionally better, these monocultures are prone to become slums over time, since they fail – or sometimes simply become uncool – all at the same time.”

Yet he also warns that when using the Transect, we must stay lean, “Form-based codes pencil when we allow the alley to be built to driveway standards, not road or highway standards. And when we don’t suck dry the wealth-building potential of placemaking by making the permitting process onerously long and complicated. Ever look back at the 19th century and wonder how our ancestors built greater neighborhoods with fewer resources? A large part of the reason is that there wasn’t a wasteful process.”

“Places that are removing the quasi-judicial process for people who create community are seeing fast, lean change. When Detroit couldn’t pay for police, it also couldn’t pay for planners and bureaucracy, and it was an interesting test of lean development ideas. Other places, like Providence, Rhode Island, are considering a permitting system in which the architect’s and engineer’s signatures are the permit, and if the development does not meet inspection for code compliance, construction stops. The city planners and architects – on both sides of the desk – then spend less time drawing and more time managing. For places not going quite so far, ensure you’ve clearly charted your subsidiarity, empowering the lowest competent level to decide.”

“Form-based codes greatly help with that, too, determining what can be approved administratively, and what needs full city council approval. They do away with the vast bureaucratic systems that consume projects, and instead rewind to 1975 with a common sense filter. Checklists make it clear that every regulation doesn’t necessarily apply to every project. Levels of appeal are embedded that are short of elected officials, and short of a court of law.”

“Plus, because form-based codes let us rethink the infrastructure requirements, as well as roll public works, zoning, and subdivision regulations into one document. We can get rid of much of the complexity, which helps us get economical. Some places are taking that to the next level, by putting in an automatic approval if a development application is deemed complete, but still not approved or disapproved within 14 days.”

“While the zoning code is where the power lies, planning should be all about enabling people to pursue their own self-defined happiness – which is intrinsically market driven.”

“Then once people are empowered to build villages again, the internet softens the disadvantages of villages by delivering shopping, entertainment and socialization. However, medical centers, universities, and other uses that use a campus sort of plan for development instead of main streets are much more expensive, because you have to get all four sides of the building right, and you cannot expand. Using the Transect to get the fronts of the buildings right along the main street lets the backs grow organically over time.”

Places that are thinking seriously about placemaking as an economic development tool, Andrés warns us, are not just thinking about how to attract more jobs. “They’re focusing on adding more tax-positive jobs. Jobs that pay enough to cover housing plus transportation costs and still have enough left to contribute to the community.” And they’re constantly thinking, “Who is trying to eat our lunch? And how do we remove barriers to character-appropriate development so that we can compete?” As those questions settle in, we realize in greater detail that placemaking is a competitive sport.

“At it’s core, walkability is a human rights issue. No one would say to a physically challenged individual, ‘Just find someone to lift you up the stairs.’ So why do we say to over 50% of the people on this continent who don’t drive, ‘Just find someone to drive you.’ Walkability is a human rights issue.”

If you’d like to listen to more lean ideas from Andrés, join us in Dallas for CNU 23 at the end of this month. For more Transect-intensive sessions within the Congress, check out:

Form-Based Code Workshop

CNU 202 day-long workshop

with Susan Henderson, Matthew Lambert, Jennifer Hurley, Marina Khoury, and Hazel Borys

Dallas, TX | Apr 29, 9am-5pm

Transect & Coding

CNU core session

with Sandy Sorlien

Dallas, TX | Apr 29, 11:30-12:30pm

GreaterPlaces Launch Party Featuring the Transect-ual Fashion Show

CNU evening event

with Greater Places (the Houzz for Urban Design)

Dallas, TX | Apr 30, 7-9pm

Happy City Applied

CNU 202 day-long workshop

with Charles Montgomery and Hazel Borys

Dallas, TX | May 2, 10am-4:30pm

If you can’t make it to Dallas, check out The Lean Transect webinar with Sandy Sorlien this Friday at 3pm eastern, or T-zones and I-zones: The character of walkable industry with me and Scott Bernstein next Wednesday at 3pm eastern. These webinars, along with Retrofitting Suburbia for 21st Century Challenges with Ellen Dunham-Jones, are free until CNU Dallas begins.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.