A Placemaking Journal

Making Sense of Community

Let’s start at the beginning. Sense of community is a legitimate thing. Or at least it was, until people like me got ahold of it.

Let’s start at the beginning. Sense of community is a legitimate thing. Or at least it was, until people like me got ahold of it.

To explain: In 1986, social psychologists David W. McMillan and David M. Chavis published their theory on what they termed “sense of community” — the feeling we experience when engaged in the meaningful pursuit of connection with others.

Here’s how they summarized it:

Sense of community is a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together.

Beyond that summary, they identified four contributory factors that make for successful community association:

- Membership. Do you feel a sense of belonging?

- Influence. Do your contributions matter? Do others’ contributions matter to you?

- Fulfillment of Needs. Are you getting what you need, however you define that?

- Shared Emotional Connection. Does the community have shared history? Do you anticipate and welcome future shared experiences as well?

Myriad bedfellows

Perhaps not surprisingly, social psychologists were not the only ones at the time exploring facets of community in America. A handful of planners and architects were doing the same. People who, for the most part, we now know as the founding members of the Congress for the New Urbanism.

Their focus was place. But in rediscovering the DNA of traditional urbanism, these designers accomplished something else as well. They uncovered principles that, informed by generations of trial and error, result in places where McMillan’s and Chavis’ ideas have legitimate potential to blossom.

Enter the marketers

Developers took notice. In building traditional neighborhoods or other urban-friendly developments, they recognized what selling folk call an “unmet need.” Starved by the nation’s overwhelmingly single-use development patterns and the physical disconnections that result, people were literally craving something most couldn’t fully identify or articulate. That is, until McMillan and Chavis gave it a name.

Sense of community.

It didn’t take long to realize that sense of community, as a phrase, was marketing gold. Not only did it resonate with the self-defined wants and needs of a very large marketplace, it equally offered an immediate and meaningful distinction from the everyday subdivisions comprising the bulk of built product.

It’s a phrase that got used a lot. And I was one of the people using it.

Mea culpa (sort of)

During the first decade of this new century I was, among other things, a marketing consultant for traditional neighborhood and urban infill developers. My job was one of making consumer introductions via marketing strategies. Helping people see themselves within a new home environment that, for many, had become unfamiliar.

Compact? Mixed-use? Mixed-type? What’s all that about?

Walkable access to commercial and recreational amenities was, of course, popular. And some people had a real penchant for competent traditional architecture. But nothing brought people into the fold better than sense of community. Perhaps because it was so absent for so many for so long.

But don’t get me wrong. I’m not looking back in retrospect and concluding we did something regret-worthy. Quite the contrary. The development vanguard at the time was indeed offering sense of community. Their physical product quite literally fostered it. Selling on that basis wasn’t just practical. It was truthful and effective.

But that’s where everything started to break down.

The highest form of flattery?

Pretty soon, sense of community was being offered by pretty much everyone — even the most banal of single-use subdivisions priced from the $220s to the $230s. Places that, by their own limiting form, were literally working against the very ideals of community — identified by McMillan and Chavis — they were touting.

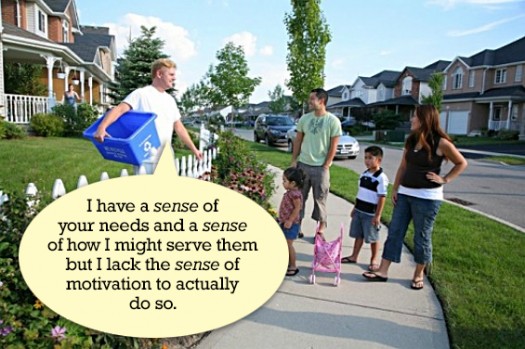

Accordingly, people started viewing sense of community not as the promise of fulfillment for a deeply held human need but, rather, as an amenity to be purchased. Just like the clubhouse and pool.

The problem is, when you purchase something, you tend to expect it to work straight out of the box. You don’t expect it to require much in the way of effort.

And community simply doesn’t work that way.

Credit: http://www.plumdeluxe.com/

Case in point

My client at one project spoke often of how he and the rest of the development team had to constantly teach people how to be neighbors.

A barking dog wouldn’t lead to a friendly chat and quick resolution across the fence. It would compel, as a first course of action, a phoned complaint to the developer, together with the expectation that it was an issue on which higher powers needed to intervene and take corrective action.

My client would always brush them off with instructions to start with the neighbor. And in time, the frequency of calls diminished as more people got connected and came to view one another in a more convivial and intimate light.

In short, people started doing the work.

Language tweaking

Fellow PlaceMaker Kaid Benfield and I enjoy an ongoing friendly debate on language — specifically whether or not some words are so over and/or misused that they need to be retired once and for all.

I’m usually the one pressing the point that wholesale removal is rash. That certain words can be played out among certain audiences but, among others, still possess valuable currency. And until I started thinking about this particular issue, I was pretty sure I’d carved out some fairly irrefutable territory.

But now, as it relates to sense of community, I think I need to side with Kaid. It’s spent. Played out. Used, abused, and run through the ringer. With all apologies to McMillan and Chavis, it needs to go.

I’m sorry about that. But there is a solution.

Sense of community might be out, but community itself is in. Because that’s the only way we’re going keep the conversational focus on the work and not just on the sensation. Which is the only way we’ll ever reach the level of true community that equates to meaningful durability and resilience.

Get into it

Sometimes people get cancer. Sometimes they fall on hard times. Sometimes the marginalized among us could benefit from the kind of political response that’s only possible when people are speaking from a united front.

A true community answers these needs. Because they’ve done the work and reached a level of interdependence in which such acts are viewed not through the lens of charity or self-service, but rather as one might view service to their own family.

So, c’mon. Join me. Stop longing for a sense of community and start seeking out community itself. Then open your heart, roll up your sleeves, and see how you might be of use.

It’ll come to be the most rewarding amenity in your life.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.