A Placemaking Journal

Lessons From Savannah

Savannah, Georgia is arguably one of, if not the most, beautiful cities in the United States. Although I lived there for a while 25 years ago, on a recent visit I was struck by the many placemaking lessons we can learn from this lovely city. In anticipation of the 2018 CNU Congress in the city, I started taking some notes of subjects I want to explore next year.

Savannah, Georgia is arguably one of, if not the most, beautiful cities in the United States. Although I lived there for a while 25 years ago, on a recent visit I was struck by the many placemaking lessons we can learn from this lovely city. In anticipation of the 2018 CNU Congress in the city, I started taking some notes of subjects I want to explore next year.

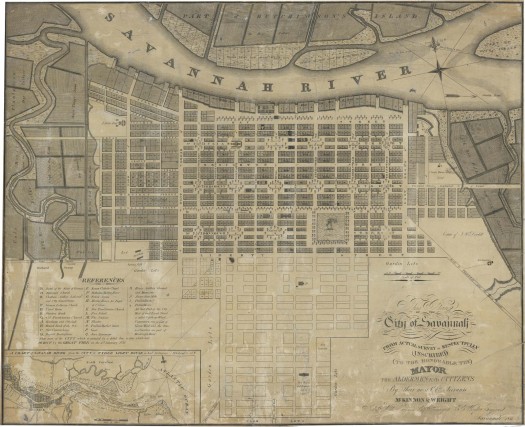

The Power of a Plan

Much has been written on the Oglethorpe Plan of Savannah, and architects and planners continue to be enlightened by the framework of public space as the plan’s first priority. The dedication of four civic parcels – trust lots – on each square, assured each neighborhood would be served by educational and religious institutions. (Reiter, B., 2016, Savannah City Plan)

Credit: Georgia Historical Society

Cities and developers struggle with the fiscal impacts of public space today, both from initial dedication and long-term maintenance. However, Savannah’s stewardship of its squares through the decades, even with loss, has been extraordinary. Out of the 24 originally planned squares, only two were lost to big box development. Of the squares that exist today, some of have been reclaimed, like the notable example of Ellis Square in 2010 from its prior use as a parking structure.

Civic Space + Civic Buildings

With the Oglethorpe Plan framework in place, the 22 squares and their diverse character puts green space at the heart of each neighborhood, or ward. We recently wrote about the trifecta of urbanism, architecture and nature, which Savannah delivers in spades.

Many of the squares have neighborhood churches on the trust lots to the east and west, or as in the image above, the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist’s Parish Center is on the northeast trust lot and the entire northwest quadrant of the tithing lots is the Cathedral site. The Independent Presbyterian Church below has a tithing lot northwest of Chippewa Square.

Even Johnson Square, with its focus on finance, maintains a crucial civic use in its southeast trust lot with Christ Church Episcopal.

The diversity of civic, residential, and commercial uses delivers almost continuous activity. The squares are busy over the weekend with people attending service, children playing while parents sit in the shade and chat, people dining and lingering at sidewalk cafés, and tourists discovering colonial history and searching for that classic scene evocative of Forrest Gump or Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. During the week, the tourist presence remains, but the squares include people taking their lunch break on a bench or students walking between classes.

Public Realm

A crucial element of the plan that nurtures livability is the public realm, or the space we use for “life between buildings.” (Gehl, 2011) Savannah has suffered through the auto-dominance of the 20th century like most American cities. Effects of prioritizing cars are particularly noticeable on Bay, Broughton, Martin Luther King Jr., Drayton and Whitaker. The one-way street system creates a level of service that isn’t safe for the pedestrian and cyclist, except on the streets that intersect squares, which provide some traffic calming.

However, even with the faster one-way streets, a sense of place is still felt thanks to the narrow rights-of-way, wide sidewalks, and building heights that together deliver the feeling of enclosure. We measured Barnard Street just south of Ellis Square, and even with 11’ travel lanes, the public realm reads like an outdoor room, thanks to the on-street parking, 15’ sidewalks, and street trees with canopies that create a ceiling.

I must confess, this is one city where I felt a little sorry for the motorists. The pedestrians have a sense of equality that keeps the drivers alert and engaged. These streets aren’t shared space, but the crosswalks are. With the exception of Broughton and Bull, my impression was the pedestrian ruled the intersection.

Private Frontages

The final issue that I’m anxious to study at CNU next year is the richness and intimacy of the private frontage. A study could be made of encroachments alone! Savannah is a city that proves the destructive power of the homogeneous 20’ front setback from most cities’ Euclidian zoning. I loved the encroachment of balconies, stoops and porches into the front yard, and in many cases, into the right-of-way.

And encroachments don’t just apply to residential uses. Savannah is generous in the private use of public sidewalks. I don’t know if this requires permitting or payment, but with many sidewalks at 15’ or wider, there is room to inhabit that space while still having a clear pedestrian zone.

I did find it interesting that Savannah made some mistakes over time, especially during the era of converting squares to parking decks and civic centers, the traffic engineering nightmare of one-way streets, and finally, an unfortunate series of public frontages. Luckily, there aren’t many of these, but because of the beauty of the architectural fabric, the mistakes are quite notable. Perhaps the most glaring is the comparison of the diagonal corners of Madison Square. On the northeast corner is the DeSoto Hilton, and on the southwest corner is the Scottish Rite Free Masonry building.

The buildings are very similar in height, but that’s where all similarity ends. The era of the Hilton’s architecture is an unfortunate example from 1968, but it’s more than the color of the brick, the proportion of the windows, or the tint of the glazing. The greatest problem with the structure is the private frontage. The setback, elevated first floor, expanses of blank walls, and lack of active use creates a dead zone on the street. In comparison, the Scottish Rite Free Masonry building turns the corner with an elegant curve and a corner entry. It doesn’t have a significant shopfront, but the regular fenestration, frequent entries, and active use on the sidewalk make all the difference.

I’m not sure if there will be a day-long Project for Code Reform Workshop in Savannah like there will be in Seattle next month, but if so, it would be much more about urban acupuncture instead of a full-on facelift. The lovely southern city is aging beautifully.

All photos are CreativeCommons ShareAlike License with Attribution to Susan Henderson at placemakers.com, unless otherwise noted. Click any image for a larger view.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.