A Placemaking Journal

Storytelling Part II: Getting to Getting Things Done

First a review:

In a post last month, I made a pitch for organizing community storytelling around getting stuff done. I acknowledged how hard it is to do that in the current political environment, which is increasingly an arena of competing tribal identities and mutually exclusive convictions:

A community that has struggled to identify and assert shared values and hopes for the future isn’t likely to provide a great context for storytelling, especially when it comes to big, ambitious ideas. Chances are, people with their own stories of disappointment and frustration, buttressed by the experience of past efforts, will have a hard time imagining their roles in a new story or see the ambitions it describes as realistic.

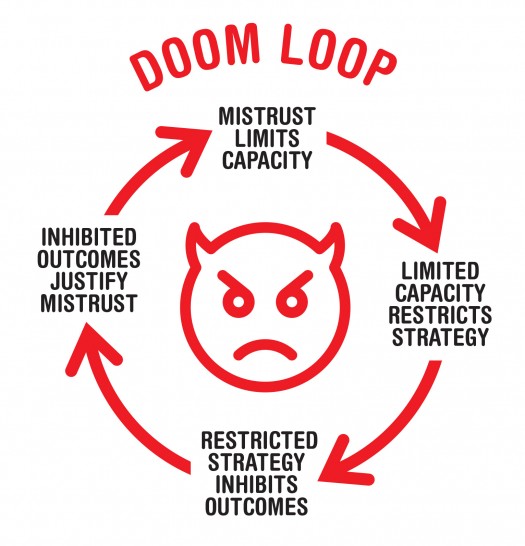

Unless you can migrate the experience of planning and implementing policies from one that under-delivers on promises to one that rewards trust with achievements, you risk getting stuck in a doom loop:

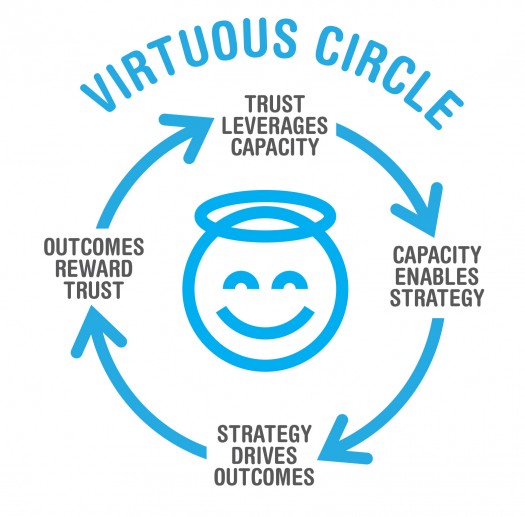

It’s a cycle that not only frustrates efforts to connect goals, strategies and outcomes in one project, it undermines faith in the people and in the tools required to get anything done anytime. A coping-with-change story needs to build a case for a “happily ever after” outcome. And that outcome has to be at a scale big enough to reverse the doom loop spin:

Yet it has to be small enough to be doable in the context the community provides. Which, in lots of cases, requires a temporary, strategic retreat:

Forget the big, hairy ideas for the time being. Pick the biggest little thing you know you can do. Do it. Celebrate that success. Then, move to the next biggest, doable challenge. Repeat until your story of competence and performance is so duh-level believable that a happily ever after ending seems plausible for the big, hairy idea you want to propose.

Let’s talk about why that’s still hard and how we might enhance the likelihood of success by strengthening the part of the story that moves between agreed-upon goals and sensible strategies.

The Struggle for Common Ground

Think of the story in three acts. The first lays out the context: characters, setting and the seeds of future action. In the second, dilemmas materialize. Which, if we’ve set up the story well, are resolved in act three.

In the kinds of stories we want to tell in community planning, we use act one to round up and analyze previous efforts, to identify key stakeholders, to figure out ways to engage them and to clarify what success will feel like to them. (Remember, the fundamental obligation of storytelling is to know the audience.)

In the second act, we consider the barriers between where we are now and where we want to go, then test potential strategies to overcome them. Out of that idea-sorting, a promising strategy – or more likely, a melding of strategies – has to emerge.

The standard for a promising strategy? Back to the key for reversing the doom loop: It must be practical enough to be within the community’s political and technical capacities to accomplish. And it has to be aspirational enough to make the effort not only worthwhile in and of itself, but also be capable of inspiring confidence for scaling up ambitions for next steps. Act three leverages that confidence to push a project across the finish line.

Too often, we don’t get to that last part with our hopes intact. It’s usually because the first two stages fail to build a stable enough foundation to support a framework for advancing ambitions big enough to justify the effort. In the round-up phase of the first act, for instance, process organizers may fail to fully account for the complexity baked into the context for planning — especially the political context.

To adequately set up second-act idea sorting, we should be close to agreement on answers to questions like these: What can we learn from previous efforts? To assure support for outcomes, who has to be at the table, and how do we get them there? What assumptions are broadly shared in the community, and where are the friction points?

In a community bruised by battles over land use and transportation policies, equity issues and affordability concerns, it can seem that there’s no common ground at all. But here’s the good news: Because we humans are social animals and because evolution has endowed us with software that allows for cooperative behavior, we have the means – if not always the inclination – to achieve agreement. Which means there’s the potential for a starting point for act one goal setting.

Aspirations for (Just About) Everywhere

The starting point for most community planning exercises is embodied, at least theoretically, in a comprehensive plan. And in a post almost five years ago, I argued that, expressed in the broadest terms, planning aspirations are so universal they can be summed up in ten promises:

We will shape future development and redevelopment through strategies that:

- Are derived from transparent processes in which all citizens have opportunities to influence outcomes;

- Respect traditions that have given the community/region its sense of place and inspired its citizens’ devotion;

- Nurture an economy that’s diverse, adaptive and capable of providing opportunities for all;

- Enhance accessibility to safe, dignified housing for citizens of all ages, incomes and physical abilities;

- Enable the full range of mobility choices, including private automobiles, transit, biking and walking;

- Foster community/regional health by reducing health risks and increasing access to sources for healthy food;

- Minimize and mitigate harmful environmental impacts;

- Increase energy efficiency and affordability at the parcel, neighborhood, community and regional levels;

- Spread the responsibilities and rewards of policy development and enforcement equitably;

- Position the community/region to attract and reward future public and private sector investment.

I’m still confident this list covers the principles or goals asserted in most community planning documents. The problem is we can’t stay at this altitude when we design a process for getting from goals to strategies to action.

The Devil (Loop) in the Details

The challenges, again, are conditioned by context. We may share values in the abstract, but the predispositions and suspicions we bring to every discussion, combined with our hard-wired nervousness about change, frustrate efforts to shape a credible story of success.

Take, for instance, the community affordability debates. There’s insistence on one side to use government’s regulatory powers to limit development for rich people and increase it for poorer populations. That’s nostalgia for an imaginary America before corporations conspired against the People. On the other side are those arguing that, unfettered from growth-stunting restrictions, the free market will fill most of the gaps. Just as the Invisible Hand provided for all in the Good ‘Ol Days, regardless of resources, race, gender, ethnicity, etc.

It takes about 20 minutes on Google to find all the examples you need of cities and regions that have tried a bunch of variations on keep-it-simple solutions and failed to make a dent in the problems. Even minor progress on affordability issues requires acknowledging bundles of complexity and the need to combine strategies – and, in more cases than we’re apt to admit, the necessity to suffer inconvenience, if not pain.

That’s from the same post in which I offered the free comp plan. For more examples of the messy debates affordability ambitions inspire, check out Todd Litman’s list in Planetizen.

Crucial to dealing with the obstacles in the way of moving the story to happily ever after is understanding this: We love analyses that imagine the complexity out of problems and skip right to “all you have to do” solutions.

If our roads are congested, all we have to do is add more lanes. If housing prices and rents soar beyond wage growth, all we have to do is bring the hammer down on developers to build what most folks can afford or build nothing at all. If well-heeled investors are gentrifying old neighborhoods, all we have to do is make it harder for them to disrupt places that should be preserved exactly as they are.

So how do we escape from the silos? What would a second-act, idea-sorting process look like if we were determined to embrace complexity and inoculate a process against unintended consequences?

The Walk and Chew Gum Mandate

Let’s use the ten universal comp plan aspirations above as the starting point for goal setting. Then, nodding to the complexity of life in general and to community planning in particular, let’s recognize that goals and the strategies to achieve them are interdependent. We can devote all our resources and energies to one goal and be confident we can deliver on at least that promise — but only by risking under-delivering or undermining on the others. We’ve got to walk and chew gum.

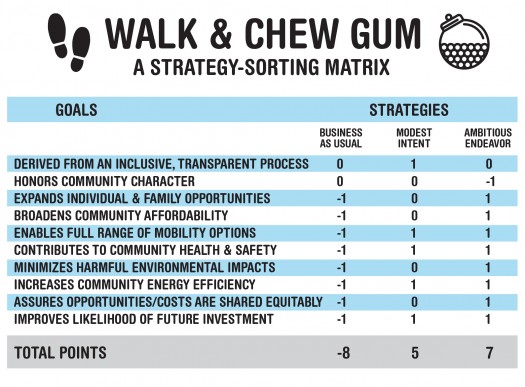

Which means measuring outcomes by the degree to which strategies support or at least have minimal impact on each of the goals we’ve determined to be essential to a success story. Check this out:

Under “Goals,” the sentences in the generic comp plan are generalized into verb phrases that shape a question for each of the strategies under consideration: Given everything we know, all the knowledge and experience we can bring to the question, what’s the likelihood that this strategy will deliver on this goal’s promise?

There are three alternative strategy sets. One is “Business as Usual.” No intervention in the status quo. Simply carry on. The other two reflect degrees of ambition. The modest set of strategies may be those for a minimally disruptive neighborhood or corridor redevelopment plan, probably responding to long-standing requests from neighborhood residents and businesses. The most ambitious approach might include the modest redevelopment effort, but in an expanded planning area requiring rezoning, transportation/parking planning and considerable public process.

The exercise requires assigning numerical values to likely outcomes for each strategy under each of the ten aspirations. A zero indicates a likelihood of no impact. A negative value (-1) suggests the strategy is likely to inhibit that goal’s achievement. A positive value (+1) suggests goal enhancement. The total under each strategy implies the cumulative potential for a strategy delivering on the whole package of hopes.

Is assigning numerical grades to likely outcomes subjective?

Of course. There’s going to be debate. The idea is to nudge that debate off the winner-take-all battleground of silo-bound arguments and into territory where information – the experience of other communities, technical data, expert analyses – has a shot at having influence and where trade-offs can be acknowledged and considered. Having to defend a prediction over what’s likely to happen if we do this as opposed to that, is way better than being allowed to veto a process that fails to affirm old, unrealistic priorities.

In the example here, I subjectively assigned values under the three strategies based on experience in community processes. The negative numbers under “Business as Usual” reflect assumptions that we wouldn’t be talking about alternative strategies if the ones in place were delivering on promises.

The moderately ambitious strategy delivers moderately effective outcomes. No negatives. But because it restricts its scope and aspirations, it earns no-impact numbers in a few categories.

The ambitious strategy pays the price for its ambitions by annoying those resistant to change. So even if it tries for an inclusive public process, it doesn’t get credit for the effort. And because it promises change to the way things are, if neighbors in the planning area weigh in, they’re likely to downgrade the “community character” effort. Yet despite those handicaps, the most comprehensive effort grades out higher.

Since I’m more interested in putting a useful tool on the table than in testing specific approaches, I purposely kept the moderate and ambitious strategy sets ambiguous. You’re invited to modify the graphic to match a project you’ve undertaken or are considering.

Refine the goals. Clarify the alternative strategies. Argue over the grades you’d assign. Let me know how it works out and how you’d improve the model.

–Ben Brown

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.