A Placemaking Journal

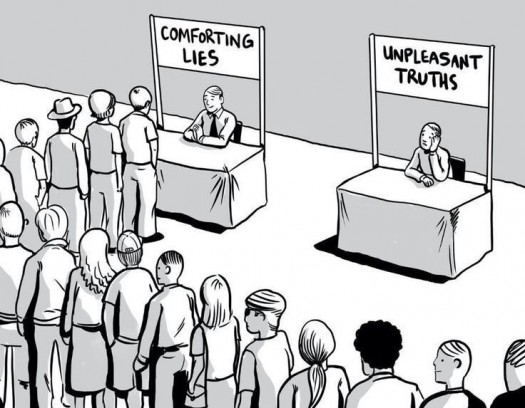

Resolved for 2018: Fewer delusions, more reality-based planning

Okay, so we’re shaking off the shock therapy of 2017 and ready to move on, right?

Okay, so we’re shaking off the shock therapy of 2017 and ready to move on, right?

Let’s start with admitting some of the stuff a lot of us got wrong about challenges and solutions in municipal and regional planning. Such as: Our misplaced overconfidence in the stability of basic institutions, especially those requiring democratic processes.

About 80 percent of the country – the 40 percent generally to right of center politically and the 40 percent generally on the left – has been forced to deal with the possibility they don’t live in the country they assumed they lived in. Disillusionment, despair and more than a little outrage rule. Which has made consensus on policy-making pretty much out of the question, not only in Washington but also in most state houses and in many county and city governments.

The partisan gap on fundamental political values — including Americans’ views on government aid to the needy, racial discrimination and immigration — is now the widest in over 20 years of Pew Research Center surveys. On 10 questions that the Center has asked in surveys since 1994 through summer 2017, the average gap between Democrats and Republicans has risen from 15 percentage points to 36 points. This gap is now much wider than the average gap on the same questions between people of different races, ages, educational backgrounds and other demographic factors.

Source: Pew Research Center, December, 2017

We’re all NIMBYs

In our cities and regions, right/left politics only partly define the polarization. When it comes to planning for growth and redevelopment, conservative-leaners and progressive types join in an unholy alliance against a common fear: fear of change. Especially change in policies that protect and prioritize private automobile mobility, single-family detached housing, exclusionary zoning and “neighborhood character.”

The New York Times’ Emily Badger sums it up for us:

These forces amount to a powerful brew: Our homes have become our wealth. Racial fears linger even if they’ve become encoded in other language. Change invariably looks like a threat. And the universe of threats has broadened from the toxic spill to the garden shadow, from the property next door to the potential development five blocks over.

I’d argue that whether we rationalize the fear from liberal or conservative perspectives, it’s an indulgence we can’t afford. Fixing what’s broken and getting stuff done in 2018 starts with recognizing change’s inevitability. While we’ve dithered over minor tweaks in transportation and land use policies over the last two decades, business-as-usual approaches have compounded problems baked into those policies. Just about every aspiration to make places more affordable and more likely to provide opportunity for more people is threatened by our failures to commit to change management.

Which gets us to this touchy topic.

We’re all gentrifiers

The toxic legacies of racism thread through American culture in lots of ways, including in the ways we use words to partition the Other from the Us. Which is one reason why so many have tended to connect “affordable housing” with “projects” and “ghettos,” the last places we’d want to end up or to live close to.

To get into a meaningful conversation about accommodating a broader range of affordability in established neighborhoods, it helps to disarm the inferences – to point to historical examples of mixed-income housing now considered among the most appealing neighborhoods in a community, for instance; or to remind people of apartments and shared houses they lived in as they made their ways up the socio-economic ladder. What’s making that discussion easier is the growing gap between household wealth and housing costs. People who consider themselves middleclass are finding themselves candidates for affordable housing defined in a broader sense stripped from implications of subsidies for the Other.

What is not getting easier is a thoughtful discussion about altering existing neighborhoods in the opposite way, by encouraging — or merely allowing — more affluent residents and businesses to move into less wealthy neighborhoods. That’s “gentrification.” Which is likely to raise property values, expand neighborhood amenities and maybe employment opportunities for existing residents. At the same time, though, an influx of affluence may also lead to higher property taxes, alter the historic character of the neighborhood and displace long-time residents no longer able to afford housing or to be comfortable with the changes.

It’s not hard to detect racist elements in the resistance of affluent residents (more likely to be white) opposing affordable housing in their neighborhoods. It’s more complicated when we’re talking about affluent (more likely to be white) people moving into low-wealth neighborhoods of color.

Black or Latino residents have just as much right to be NIMBYs as white people. And given the experience of minorities when it comes to dealing with the social and economic priorities of white folks, black and Latino residents of gentrifying neighborhoods have more than enough historical evidence to suspect racist subtexts in every conversation. Here’s an irony: Anti-gentrification activists who live in those neighborhoods can usually count on the vocal support of liberal white folks, including many who are fighting affordable housing in their own (mostly white) neighborhoods. Here, after all, is a NIMBY cause untainted by racism.

Except for the potentially disquieting realization that the even more logical ally of the anti-gentrification contingent is the one made up of all the racists who’ve ever lived.

The whole point of racism, after all, is to isolate the Other from opportunity and protections afforded the privileged Us. I’d be curious to hear how a minority neighborhood protected from majority influences might differ from a minority neighborhood deprived of majority investment.

Jason Segedy gets at the problem in a piece for CityObserver:

The degree to which these fledgling positive examples of private reinvestment in long-neglected neighborhoods have truly taken root and have begun to influence regional housing markets is still uncertain. As for documented cases of low-income residents being uprooted and displaced by spiraling housing costs – these have proven even more elusive.

While it can be unclear whether the return of middle class and affluent residents to a neighborhood will really do anything to improve economic conditions for the poor, it is an ironclad certainty that a continued lack of socioeconomic diversity, and its concomitant concentrated poverty, will improve nothing and help no one in these cities – the poor most of all.

In previous posts about neighborhood change and gentrification, my PlaceMakers partner, Scott Doyon, gently nudges us to remember how neighborhoods are always in flux and how many of us at one time or another play the role of the gentrifiers or the gentrified. The danger is in institutionalizing the Other/Us partitions:

If your neighborhood is divvied up as old vs. new, or rich vs. poor, or white collar vs. blue collar, or black vs. white, or any number of ways people succumb to their most divisive and least appealing tendencies, and your actions serve to reinforce those distinctions rather than overcome them then, well, good luck with that.

Managing change, directing it, channeling it, or even mitigating it is no small endeavor. But neighborhoods in transition have the opportunity to try. To commit themselves to pursuing reality-based strategies that respectfully unite people, leverage their talents and resources, mitigate conflicts, and prevent what’s ultimately the worst possible outcome at either end of the spectrum: monoculture.

But it only works if everyone — of every status — works together. Wherever you sit in the equation, us vs. them simply ain’t gonna cut it.

Here’s an idea: If we want community diversity, opportunity, investment – all with minimal forced displacement, instead of declaring war on change, why not focus rescue strategies on those most vulnerable to being forced out of gentrifying communities? If we’re not sure who and how many are vulnerable – and we aren’t – why not put more effort into figuring that out? And then into targeting programs to serve those most like to suffer?

That gets us the third delusion we need to confess.

We are all tax dodgers

That big gap we keep talking about, the one between household wealth and cost of living, has been growing for more than three decades. It started about the time the US economy entered a post-industrial era where “service economy” – which includes high-wage professionals of all types as well as low-wage workers – better defined how most Americans made their money.

Not just wages either. The service economy also includes all the ways people make money from their money. (You know, mo money, mo money.)

These days, the category of investment earnings has a lot to do with the difference in household wealth between the richest 20 percent of the country and everybody else. Consider: A million bucks parked in an S&P 500 index fund made more than three times the earnings of the median American household in 2017.

It’s a differential that should send out alarms. Especially since investment earnings enjoy tax protections wages don’t. So you’d think there would be a lot of resentment about that and a lot of pressure for government intervention to rebalance the way earnings are treated, taxes are gamed and services are subsidized. And there is. But what inhibits consideration of meaningful policy changes is a countervailing resentment shared by most Americans – the resentment of government.

As has been the case for the last decade, public trust in government remains near historically low levels. Just two-in-ten Americans say they can trust the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always” (4%) or “most of the time” (16%). Nearly seven-in-ten (68%) say they trust the government to do what’s right only some of the time and 11% volunteer the response that they never trust the government.

Source: Pew Research Center, May, 2017

We tend to invest more trust in government as government gets closer to home. But those of us who work in and for municipalities and counties know the resentment even at the local level is daunting. And too often overwhelming when strategies to ameliorate the unwelcome impacts of change require investment of taxpayer money. Even when government provides the only potential for solutions at the scale we demand. The only gap growing bigger than the one between household wealth and the cost of living is the one growing between what we expect from government and what we’re willing to pay.

I don’t expect there to be a radical turnaround in 2018. But I think it’s a healthy sign that we’re nearing peak frustration. We running out of rationalizations for avoiding the hard work required to shape places that are safer, more accessible and more opportunity-filled for more people.

My resolution in 2018 is to make better use of this blog space to shine a light on people and on approaches offering hope for narrowing the gaps between what we say we want and how we achieve it.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.