A Placemaking Journal

Building a Custom, Multi-Century House for Under $80 a Square Foot

Affordability is a tough nut to crack. For decades, the production housing industry has operated under a simple premise: Americans value space above all else. If you want to make a house more affordable, you build the same house with lower quality materials and cheaper details.

Affordability is a tough nut to crack. For decades, the production housing industry has operated under a simple premise: Americans value space above all else. If you want to make a house more affordable, you build the same house with lower quality materials and cheaper details.

Goodbye four-sides brick, hello one-side brick. Or no-sides brick.

It’s a perfectly sensical approach and, for some folks, it works out just fine. They get more house for the money and, because it’s new, it’s likely to last at least as long as they plan to live there. In short, it’s affordable. For now.

Disposable dwellings are one, albeit shortsighted, way to meet the need for affordability but today I’m more focused on those whose needs are not being met. Those of average means who would prefer not to trade quality. Those concerned with energy costs and the long-term durability of their investments. Those inspired by sustainable, indigenous materials and the endearing imperfections of work-done-by-hand.

Today I have a story for them. For you, perhaps. A story of one man who, in his own words, is “subverting conventional building practice with an act of permanence, constructing an energy-efficient, multi-century legacy home for the price of a vinyl-clad, production-built box.”

Could this House Change the World?

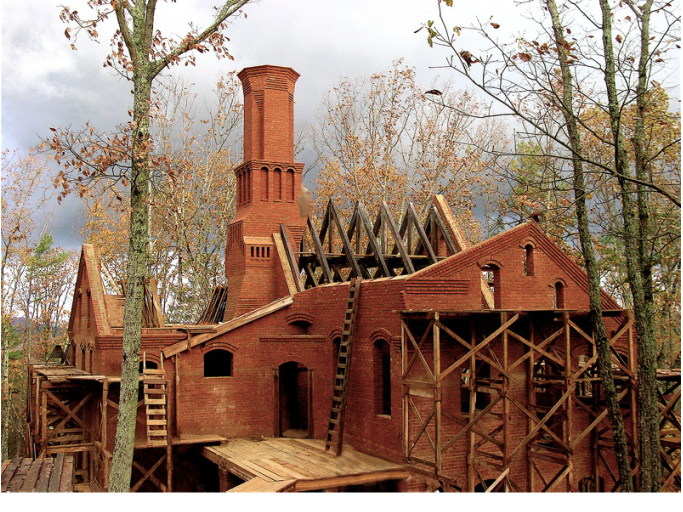

Don’t let the pictures fool you. The activity taking place on this rolling, 40-acre spread on the rural edges of Columbus, Georgia, may look like any other house being built but looks can be deceiving. It’s actually a grand experiment. A great leap backwards to take us forward once again.

This is the future site of the Adams House, a 3,000 square foot, structural masonry and timber frame home centered on a grand fireplace that, if everything plays out as planned (and hoped), will be completed for just under $80 a square foot.

In return for that investment, its buyers will receive a rock-solid, practical, custom-built home whose shelf life can be measured in centuries.

Meet Clay Chapman

Clay Chapman is not an architect. He’s not even a homebuilder, really. At least not in the production-oriented way we consider those terms today. He’s more like an artifact from a simpler time — a “field architect,” so to speak. A craftsman who, in the practical application of his trade, was taught the basic patterns of timeless architecture which, in turn, have become the basis for his own designs. Designs that have proven rich in sweat, sense and soul.

Clay Chapman is not an architect. He’s not even a homebuilder, really. At least not in the production-oriented way we consider those terms today. He’s more like an artifact from a simpler time — a “field architect,” so to speak. A craftsman who, in the practical application of his trade, was taught the basic patterns of timeless architecture which, in turn, have become the basis for his own designs. Designs that have proven rich in sweat, sense and soul.

He developed his skills as an itinerant builder, raising wooden stables for the rural gentry, until he realized just how much abuse a horse could actually inflict on a building. That’s when he turned to structural masonry, which he found to be “design with 1,200 pound animals in mind.”

He developed his skills as an itinerant builder, raising wooden stables for the rural gentry, until he realized just how much abuse a horse could actually inflict on a building. That’s when he turned to structural masonry, which he found to be “design with 1,200 pound animals in mind.”

For the uninitiated, structural masonry is construction in which brick or stone walls bear the full weight of the building, as opposed to simply serving as a cosmetic veneer for a frame constructed by other means. Chapman lays bricks three brick deep, giving his walls 12 inches of regulating thermal mass. The rest of the building rests upon them.

In time, his increasingly substantial stables gave way to custom homes for well-heeled exurbanites and deep-pocketed townies. The results, without doubt, have been works of purity and great beauty but there’s something else you need to know for this story to make sense. Chapman, you see, views every house he builds as a small contribution towards a greater good — a dream of reforming how we build — and there was one none-too-minor aspect of his work that challenged that goal: its cost.

In short, building meticulously detailed homes for wealthy patrons might provide for a comfortable living but it wasn’t going to impact industry norms in any meaningful way. Yes, historically-speaking, buildings of the noble and well-born have always served to educate, inspire and drive innovation (and, for the artist, present wonderful opportunities), but what really distinguishes our historic building stock from today’s disposable landscape is the skill, durability and practical wisdom embedded in its everyday buildings of common men.

I wonder, he thought, if the benefits of structural masonry construction — its permanence, beauty and gentle environmental footprint — could be made attainable, readily so, to the middle class.

So he set out to do what tradesmen have always done: Try it and find out.

Making It Work

For years, Andrés Duany has been pointing out that the finest, most lasting assets of America’s built history were completed at a time when we had comparatively less wealth. Nonetheless, people routinely dismiss old, solid buildings with the suggestion that “no one can afford to build like that anymore.”

So which is it?

For Chapman, everything is relative. It’s not about whether such methods are affordable or not affordable. It’s about the design choices you make along the way, and the manner in which you embrace the masonry rather than simply viewing it as a feature in an otherwise conventional home. Chapman sums it up like this:

“At the building envelope, the ‘one step’ based structural masonry process can replace nine steps required for conventional building: framing, sheathing, wrapping, siding, exterior paint, insulation, dry-wall, interior paint and the majority of trim.”

That’s a promising start. And from there, his ambition to keep the house under $80 a foot — on par with that of everyday, conventional tract housing — drives other design choices.

For example, masonry corners are labor intensive, which adds disproportionately to cost, so the Adams House is a classic, 4-sided box. That may sound like a concession, but it isn’t. Think in terms of homes historically. More often than not, they also started out as a box, then grew over time via smaller boxes added on. We may have become indoctrinated by the idea that over-articulation is necessary but it’s simply not the case. Scale, balance, and the manner in which a building’s variations catch light all contribute greatly to its dignity and presence.

Then there’s the daylight basement. To build the ground level and second story as a 2,000 square foot house on a slab would have averaged out to roughly a hundred dollars a foot (or more) but by adding a basement, finished out, you gain 1,000 additional square feet of living space for only modest additional cost.

Finally, there’s windows. Chapman loves them, and has included 50 in this one design. When cost is not the driving factor, he’d typically top each window, or bank of windows, with an arch to maintain the high design and structural integrity of the building. That might run $400 for a four foot span. To reduce cost, he might employ steel lintels instead which, to cover the three-brick thickness he builds with, would be about $100. In this case, however, he wondered what would happen if he employed slabs of finished granite (see photo above) for window headers. Turns out, they run about a buck an inch, or just under $50 for the four foot span. The end result? Functional elegance, more than 85% off. A creative cost savings that, taken with the others, allows for certain indulgences. For example, the Adams House will contain no drywall. All interior partitions are being constructed of solid, tongue and groove planking.

The Adams House project is full of stories like these. Here’s another. When I visited, Chapman was nearing completion of a small outbuilding about 100 yards from where the house will be. Why? Because, during construction, he likes to live on the job site and needs a place to sleep. He gets up each day, makes coffee over a campfire, and lays brick. When the house is done, the cabin will become a studio, retreat or playhouse for the owners.

This is the point at which you start to realize that Clay Chapman exists in some sort of alternate universe, doing things totally alien to how we now think of homebuilding. The things you see when you watch him work, or hear when you talk with him, seem impossible or, at the very least, impractical. And yet he’s doing it.

As no shortage of people struggle with delivering solid, dignified housing for an affordable cost, he’s doing it. And then some. Providing a home of true permanence, capable of lasting for as long as it remains loved, at a price suited to the middle class.

All of this raises an interesting point. For some time, we’ve been expecting housing innovation to somehow emerge from otherwise conventional circles and yet, in other aspects of business, we routinely assume that innovation will be driven not by the entrenched but by hungrier, more flexible, more creative outsiders.

The challenges of affordability, durability, and beauty could be well served by such outsiders. And I think I’ve just stumbled upon one of them.

Hope for Architecture

Last year, Clay met “Original Green” author Steve Mouzon who, like a number of others, has worked tirelessly in support of traditional building and has achieved small-scale affordability through his work with the Katrina Cottage movement. Mouzon recognized immediately that affordable permanence, equally implementable from the rolling, subsistence farm in the countryside to the tightly-knit, walkable city neighborhood, was the “holy grail” he’s long sought.

His encouragement proved propulsive. In response, and despite his discomfort with self-promotion, Chapman has launched “Hope for Architecture,” a documentary and blog effort to chronicle his ongoing progress on the Adams House and make its lessons learned available to others.

Visit him, check out his body of work, follow his efforts on Facebook, and share this blog post. His story is the tree falling in the forest.

It deserves to be heard.

(A lot has happened with the house since this story posted. Read the next chapter here.)

–Scott Doyon

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.