A Placemaking Journal

Elevate Your Thinking: Light, air and connectivity beyond the street

As we increasingly urbanize, relearning the craft of creating human-scaled places, I often — too often — hear that “if we just get the ground floor right” then all will be fine. While obviously a good start, and one that addresses the most immediate of pedestrian interests, I find that this line of thinking ultimately allows, even incentivizes, buildings poorly designed above the first floor, thereby marginalizing the complete urban experience.

As we increasingly urbanize, relearning the craft of creating human-scaled places, I often — too often — hear that “if we just get the ground floor right” then all will be fine. While obviously a good start, and one that addresses the most immediate of pedestrian interests, I find that this line of thinking ultimately allows, even incentivizes, buildings poorly designed above the first floor, thereby marginalizing the complete urban experience.

The crescendo of urbanism? Nope, there is more to it!

Nice enough… (Photo credit: Urbdezine.com)

But after a while… a little monotonous. (Photo credit: Urbdezine.com)

Case-in-point: San Diego architect Ted Smith is attempting to change downtown San Diego’s regulatory requirement for zero foot setbacks on all property lines, even those interior to the block. Our narrow 200’ x 300’, sans-alley blocks were originally laid out to produce the greatest number of higher-renting corner lots possible throughout downtown. The downtown Community Plan, updated in 2005, emphasized zero foot setbacks along the streetwall in order to “get the street right.” However, as our city continues to incrementally fill up with mid-rise buildings that maximize the zero-setback on all sides of the building envelope, the upper floors are not being built with the basic need for proper light and air access, something necessary to ‘humanize’ the block.

In focussing on getting the street right, we’ve lost sight of the 3-dimensional ramifications of building 6-story, 85-foot tall, Type III construction buildings on 10 – 15,000 sq. ft. lots with large, expensive, tightly stacked units. The maximization of profit potential within our legal building envelopes is causing the latest neighbor-to-neighbor conflicts over proper light, air and the need for private space within the block itself.

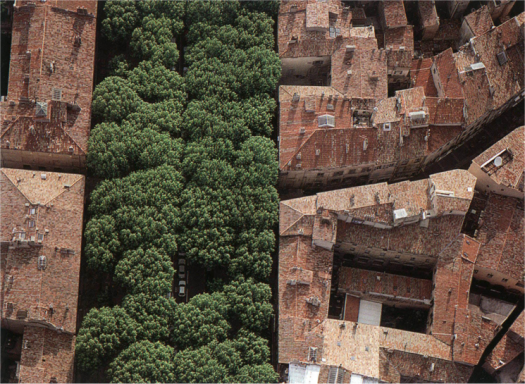

Maxing out the block in San Diego.

Making it impossible to cross-ventilate, let alone enjoy. (Photo credit: Ted Smith)

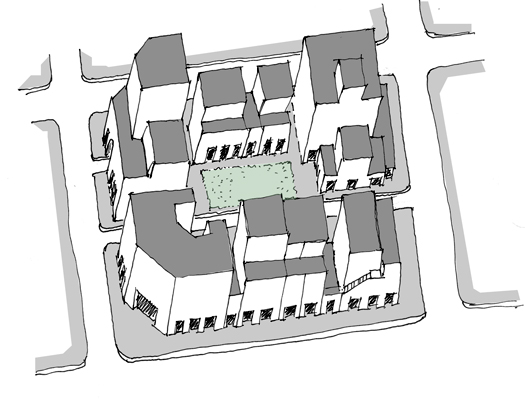

The interior of the block is not throw-away space. It’s another vital realm where urbanism occurs and, traditionally, has contained spaces where people live, play, work and relax. While we may never achieve a New Orleans’ mid-block courtyard pattern, our regulations should foster a greater diversity of building types — not just towers and full-block buildings, but also the more organic perimeter or liner block buildings with courts and stepbacks interior to the block.

Livable, functional space, at both the public and private level.

Perimeter block buildings, creating livable interior space.

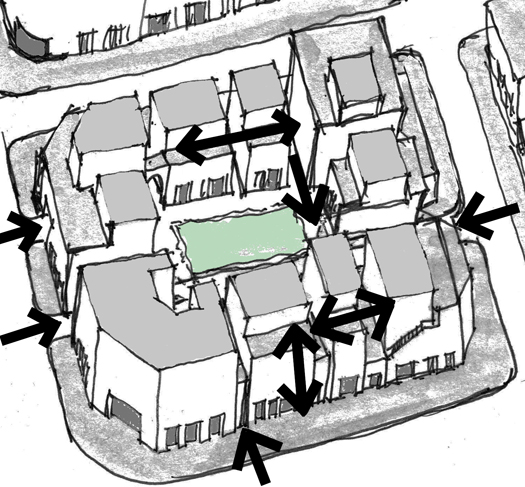

Another important design element, beyond getting the ground floor right, is designing the upper floors to be connected with the block, street and other buildings. A few very good San Diego’ architects are beginning to experiment with the opportunity to connect people and deftly share common spaces and views. See my previous posts on the Next Urbanism here and here regarding this urban design condition.

Exploring connectivity beyond street level. A perimeter block building in San Diego’s East Village.

Over time, we can increasingly consider light, air, and connectivity at all levels, creating a more civilized and humane urbanism.

Connectivity, beyond the ground floor, is important to building the City 2.0. Our cities are not simply a connection of ground floor streetscapes, but a series of complex connections filled with people, places, and fun. Healthy cities need to balance the ground, upper and lower floors to avoid conflicts and create places that people enjoy. Ultimately, moving beyond the ground floor is about how we’re able to physically connect with others that will ensure our ability to not only endure but thrive in the 21st century.

Civilized blocks add up to… you guessed it: civilization. (Photo credit: Steve Mouzon)

–Howard Blackson

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.