A Placemaking Journal

Corrosion of Community: Impossible standards as an excuse for inaction

Community fascinates me. Not just the idea of it, but the dynamics, and how those dynamics end up stoking or choking our collective efforts to be together. Having worked in a lot of different places, I’ve had opportunity to study community in action, at both its strongest and weakest, in all different contexts — economic, political, cultural — and have tried to identify patterns that lead to results.

Community fascinates me. Not just the idea of it, but the dynamics, and how those dynamics end up stoking or choking our collective efforts to be together. Having worked in a lot of different places, I’ve had opportunity to study community in action, at both its strongest and weakest, in all different contexts — economic, political, cultural — and have tried to identify patterns that lead to results.

I wrote about a series of these back in October. Not ways to create community, mind you, but ways to foster it. Ways that cities and towns can aid our instinctive urge to connect and co-exist in productive relationship.

It’s not about kumbaya or chamber of commerce photo ops. It’s about survival. I, together with a growing body of research, view the relative strength or weakness of community ties as an indicator, perhaps the most critical indicator, of resilience. Not unlike John Michael Greer who, in his handy post-industrial how-to, The Long Descent: A User’s Guide to the End of the Industrial Age, asserts “the community, not the individual, is the basic unit of human survival. History shows that local communities can flourish while empires fall around them.”

Not a small deal. In short, our ability to keep on keepin’ on may, at its most fundamental levels, come down to how well we’re connected.

Corrosive forces

How to help build community up is one thing, but what about factors that tend to tear it down? What about the things that stand in the way of meaningful progress? Things that draw and lock us into perpetual and unproductive stasis?

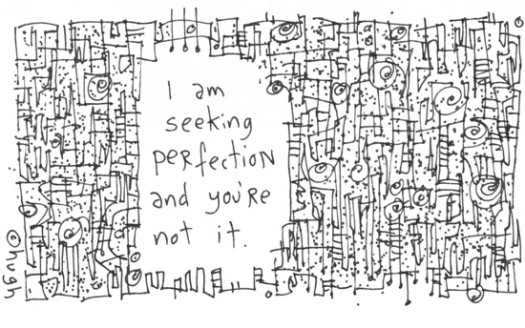

Those are equally interesting. So today I identify the first of what will probably be more to come: Measuring success against impossible ideals rather than achievable goals.

This instinct is seemingly epidemic and unrelated to affluence. It plays out like this: Say your city, town, neighborhood or other collection of folks working together, accomplishes something. For example, let’s say it manages to get bike lanes installed on a primary route through town.

From my vantage point, which includes study of near-countless communities doing similar things, I’d see it as a huge win. I’d see something people should take great pride in and use to propel their momentum forward. After all, consider the likely dynamics involved: an all-powerful state DOT; the ability to secure funding; the personal agendas of city leaders; the challenges of allocating limited public space; adjacent residents confronted with the possibility of change; and the ever-present belief by most people that more car lanes equals less traffic.

Despite all that, each a formidable obstacle in and of itself, it got done. Yet, what do the corrosive forces have to say about it? Why, it’s a failure for any number of reasons. It’s just one route, rather than a network of bike lanes. They ended up just four and a half feet wide rather than the more ideal five. They displaced driving space or include segments with sharrows.

Whatever the reason, the underlying position remains the same: Even for those ideologically in favor of the effort, the project is a failure because it falls some degree short of perfect. As though perfect were ever a possible outcome.

This is ludicrous. People making the conscious decision to work together, to put their differences aside in pursuit of shared interests, to find initiatives with the potential to improve quality of life (and, with it, economic, social and/or environmental performance), and to navigate obstacles to actually get something done, constitutes success. Grand success. Why? Because it so greatly exceeds what can be reasonably expected in the course of the day-in, day-out operations of most places.

I’ve seen plenty of places where, for a host of reasons, nothing ever gets better. Day to day operations are managed, people go about their business, yet no investments in the future viability of the community ever seem to materialize.

This is what one should reasonably expect to happen in Anytown, USA. Thus, this is the bar against which proactive efforts should be measured.

If your city or town is getting things done, consider yourself lucky. It’s a lot more rare than you think. And if you possess some particular insight into how such initiatives could be even better, leave the comfort of your armchair and get in the game.

It’s actually quite simple: If the efforts around you are lacking and you know how to improve them but fail to contribute, the problem isn’t those working to make things happen.

It’s you.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.