A Placemaking Journal

NIMBY, I Hardly Knew Ye

Last week I stepped back in time a bit to revisit the idea of NIMBYs (Not In My Back Yard opponents to development) and consider anew whether their tenacious aversions earn them the lauding of heroes or the disdain we reserve for villains and scoundrels.

Last week I stepped back in time a bit to revisit the idea of NIMBYs (Not In My Back Yard opponents to development) and consider anew whether their tenacious aversions earn them the lauding of heroes or the disdain we reserve for villains and scoundrels.

As I said then, in many cases, NIMBYs have kept the world from becoming a worse place, and that’s no small feat. But they’ve also kept the world from becoming a better place because their reactionary nature can’t seem to tell the difference between bad change and good.

When your common foe is change alone, in whatever form, everything looks like a problem. A perpetual stream of dissatisfactions in which endeavor of any kind — however benign — is received as the work of some oppressor while everyday citizens helplessly assume their ceaseless role as victims.

But is that really what makes community work? To coalesce and get things done? Even for the most cynical, the least trusting, and the legitimately aggrieved, isn’t that shtick getting just a little bit old?

So which is it?

Conveniently, today marks the end of an exhausting, 18 month election cycle. One in which the common ground among Americans, if there’s been any, can likely be found in shared frustrations over gridlock and inertia.

Wherever we sit politically, one refrain seems curiously consistent: Government’s not getting anything done.

If that’s at the heart of why we’re all so ticked off, you’d think we’d have a predilection for action. And for working together. And our communities, where we literally possess direct means to make things happen, would be laboratories for responsiveness, experimentation, and progress.

But no. As it turns out, the opposite of a do-nothing Congress is not a do-something community. Not at all. By all appearances, the opposite of a do-nothing Congress is simply a place where it’s the citizens, rather than the government, who conspire to stop time and keep anything from ever happening.

Downhill from there

When I considered the issue five years ago, I held out hope that the many positive attributes of the NIMBY movement — its ability to rally people, for instance — could be harnessed for good. That its adherents could evolve in their service to the communities they purportedly love from a default position of no on everything to one of yes, given the right circumstances. And that that shift in mindset could then forge the way towards taking on the real work: the work of consensus-building around meaningful goals, followed by the strategies and tactics necessary to achieve them.

That doesn’t appear to have been the case, however. And at least one reason why, which I never saw coming, has somewhat ironically been the tool that ties us all together like never before: social media.

Fueling the fire

Social media is an amplifier. It takes our frame of mind and projects it outward to hundreds, if not thousands, of people. And with its rise, we’ve found an interesting dynamic. One where our petty daily frustrations and annoyances — things that might historically have been voiced and discussed informally in person among small groups of family, friends, or neighbors — suddenly rise to the level of shared community considerations.

So what’s wrong with that? Ask a lot of people and they’ll tell you it’s democracy in its purest form. And I suppose that’s true. But it’s a deceptive democracy. One that lulls people into the false belief that shared commiseration, in and of itself, constitutes a meaningful form of civic contribution.

That’s an idea that would be laughable if it wasn’t so dangerous and corrosive. It’s almost the exact opposite outcome of what I optimistically envisioned when considering the potential promise of NIMBYs five years ago.

NIMBY 2.0: All the same frustration and outrage, yet none of the follow-through action. I mean, at least classic NIMBYs, even the most obstructionist among them, rose to the level of actually doing something.

What’s it all add up to?

These are thoughts I’ve had on a slow simmer for quite some time. It’s a lot to digest and think about, and every time I study or travel to a new community, I gain increased perspective on how these dynamics play out in different places, among different people of different circumstances.

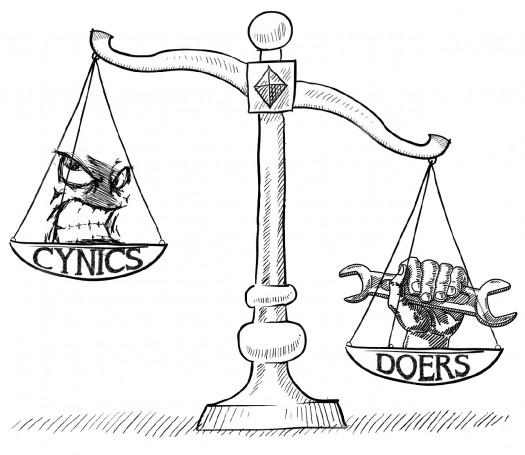

From it all, I’ve come up with one thing that seems remarkably consistent across the board: In every community, there’s a tension between those who do and those who don’t. Those motivated towards action and those motivated towards reaction. And when the latter drowns out the former — be it in numbers or just in volume — that’s when community starts to falter. Because that’s when we increasingly become a collection of dissatisfied consumers, fueling our shared discontent, rather than one of engaged and contributing citizens with an acknowledged and respected interdependence.

Of course, none of this is to suggest that, in a healthy culture of doing, all the doing would necessarily be positive. Or appreciated. Or to everyone’s liking. Some doing would invariably suck. And all kinds of people would get frustrated. But that, ideally, would then inspire them to help redirect the conversation with action of their own, perpetuating an ethos of getting somewhere.

In an odd sort of way, I’m almost nostalgic for the NIMBYs of yore. When I wrote last on the subject, I was looking at how we might channel their action towards more positive outcomes.

Today, in many ways, I’m wondering how to compel any action at all.

If PlaceShakers is our soapbox, our Facebook page is where we step down, grab a drink and enjoy a little conversation. Looking for a heads-up on the latest community-building news and perspective from around the web? Click through and “Like” us and we’ll keep you in the loop.